Actors Who Got Their Directors Fired

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Aside from the world of politics, there is probably no greater arena for the clash of egos than a Hollywood film set. The tabloid industry grew almost entirely out of reporting on industry feuds, and there were none juicier than when a star would pull rank and get their own director booted from a project. It didn't happen a lot, but when it did it made huge waves, to the point where the Directors Guild eventually had to intervene and limit the scope of a star's power. But it wouldn't be Hollywood if there weren't some great behind-the-scenes stories, right? Here are the actors who got their directors fired.

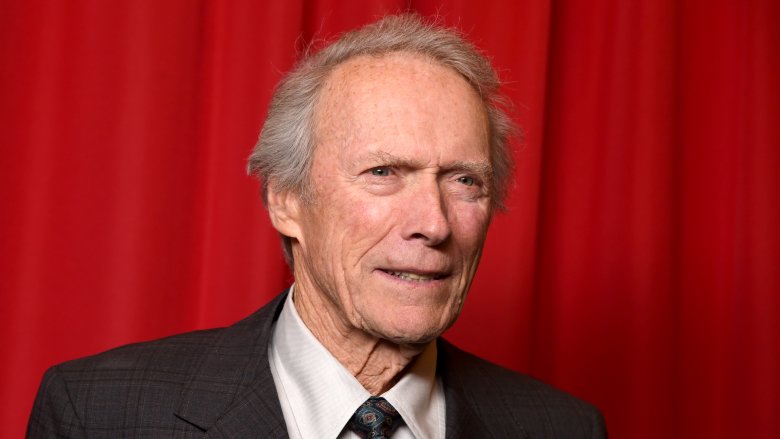

Clint Eastwood

As we just mentioned, in 1976, the Directors Guild implemented "a strict set of guidelines aimed at protecting the financial and creative rights of its members," according to How Stuff Works. What this meant in practice was that "no actor, producer or other person engaged in a film may fire the film's director and assume his duties and title." The rule became known as "The Eastwood Rule," as a result of the conflict between Clint Eastwood and The Outlaw Josey Wales director, Philip Kaufman.

Eastwood famously relieved Kaufman of his directing duties just two weeks into shooting after allegedly growing frustrated with Kaufman's "slow, methodical style and unwavering desire to create the perfect shot, no matter how much time it took." Eastwood replaced Kaufman with himself, but Kaufman retained the screenwriting credit. Decades later, in an interview with Venice Magazine, Kaufman shed some light — and some serious shade — on the whole situation. "Clint, for whatever reason, decided we had some creative differences. He was the producer. He was the biggest star in the world. One of us had to go. (laughs) It wasn't my choice, so...I've never seen it, actually. I hear it's very good." Apparently Eastwood also felt it was an effective move, because...

Kaufman's directorial scalp wasn't the only one Eastwood would claim

Director Bruce Beresford felt the full force of Eastwood's star power when he was ousted, er, "left" The Bridges of Madison County after "creative differences" with the film's lead. Though the eponymous rule blocked Eastwood from firing Beresford directly, his backchanneling against the director — specifically in terms of his insistence on casting Meryl Streep to play opposite him over Beresford's preferred choices of Lena Olin or Isabella Rossellini, according to TCM — was enough to get Beresford to leave the film.

Beresford confirmed the hostile environment in an interview with The Border Mail during which he said, "The reason I didn't do Madison County was that although I worked on it for about a year, Clint Eastwood wanted to direct it. He was always sort of polite in a rather off-hand way but he was basically uncooperative when I was preparing it and I finally went to the studio and I said Look It's never gonna work like this. I said you better let Clint direct it and I'll go. I just pulled out." Is anyone else surprised that Dirty Harry sort of sounds like a teenager who sulks until he gets his way in this scenario?

Clark Gable

Gone with the Wind is full of high drama set to the backdrop of The Civil War. And apparently, the production of the film was also something of a battlefield, including massive fights over casting, scripting, and of course, directing. In his account of the behind-the-scenes turmoil, which he describes as "Hollywood's biggest scandal," film critic Emanuel Levy chronicles the rancor between lead actor Clark Gable and the film's original director, George Cukor. "There is no doubt that Gable's dislike of Cukor contributed to his dismissal," Levy writes. Apparently Gable "protested vigorously at MGM" that Cukor was more of a "woman's director," which at the time was a pejorative concept that lead Gable to believe his role in the film would be diminished as a result.

But it wasn't entirely Gable's dislike of Cukor that got him bounced from the film. Cukor's longtime friend and legendary producer, David O. Selznick, was the man who made the final call on Cukor's termination. Cukor and Selznick battled from the start over Selznick's micro-management of the film, including his insistence on reviewing "the block rehearsal of each scene before it was shot," meaning Cukor couldn't even yell "Action!" without Selznick's approval. Cukor, of course, pushed back on Selznick's meddling, leading to an increasingly tense environment on set. On top of that, Selznick had campaigned hard to get Gable to do the film, leaving Gable in a position of considerable leverage when it came to his gripes about Cukor. In the end, Gable won Selznick over. Cukor was out, and replaced with Victor Fleming.

But Cukor didn't go out without a parting shot. Levy writes that Cukor once told a reporter, "It is nonsense to say that I was giving too much attention to Vivien and Olivia [the film's female leads]. It is the text that dictates where the emphasis should go. Gable didn't have a great deal of confidence in himself as an actor, although he was a great screen personality; maybe he thought that I didn't understand that."

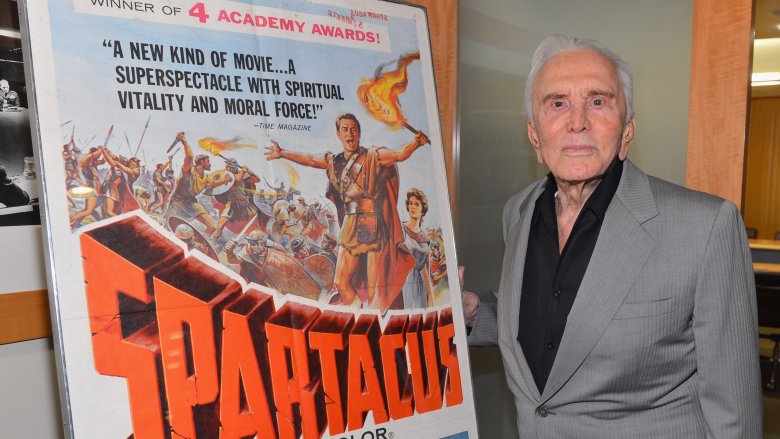

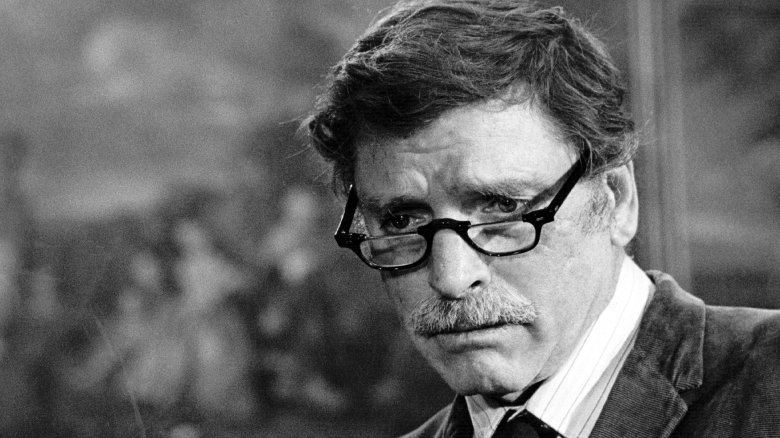

Kirk Douglas

Another actor-director spat of lore was the one between Kirk Douglas and Anthony Mann on the set of the gladiator epic, Spartacus. According to most accounts, including this one by TCM, Douglas was never happy with the studio's choice of Mann as a director. "He seemed scared of the scope of the picture. I fought with the studio to replace him. But they had done well financially with him, and ignored all my pleas," Douglas said. After a few weeks of shooting, Douglas' suspicions about Mann's directorial deficiencies seemed to be confirmed, and Mann was replaced with Stanley Kubrick, who Douglas' had been pitching to direct all along.

Though Mann's axing has consistently been laid at Douglas' feet (since he also served as exec producer on the film), Douglas clarified what really happened in his 2012 book, I Am Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Douglas wrote in the memoir, "I'm no Donald Trump, but I did it," apparently referencing the famous catchphrase from The Apprentice. Douglas continued, "He was so gracious, and I said, 'I owe you a picture,' and a few years later I did a picture with him." That's not exactly the bad blood scenario it has always been portrayed as, and in fact, that film that Douglas and Mann finally made together, The Heroes of Telemark (1965), ended up being the last "completed film" of Mann's career. He died three years later in the middle of production on A Dandy in Aspic.

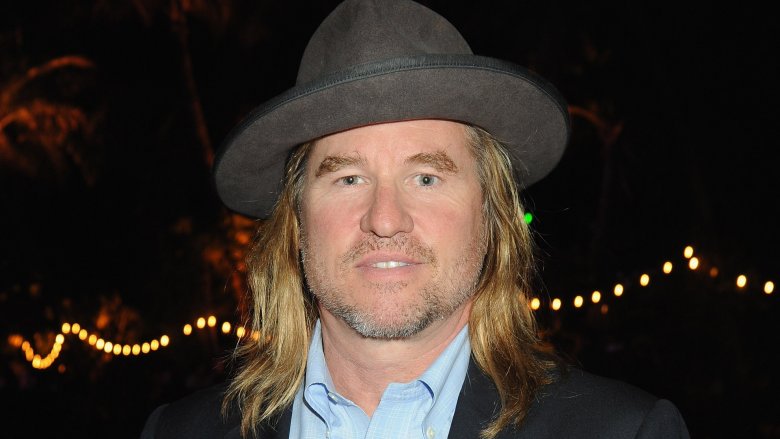

Val Kilmer

The Island of Dr. Moreau holds a place in cinematic history as one of the worst films ever made, despite the fact that it was painstakingly adapted and shepherded by director Richard Stanley over the course of four years. But that apparently meant nothing to Val Kilmer, who helped torpedo Stanley's set with "rude and abrasive" behavior, including an instance during a scene in which he "sat on the ground and refused to stand up," according to The Telegraph. In addition to other elements hinting at Stanley's inability control of his production — like the temporary exit of star Marlon Brando, and disastrous weather elements — Kilmer's behavior was the last straw for studio execs who eventually replaced Stanley with veteran director John Frankenheimer just three days after shooting began.

But Kilmer proved to be just as much of a nuisance for Frankenheimer, who allegedly later remarked, "Even if I was directing a film called The Life of Val Kilmer, I wouldn't have that p***k in it." In his own defense during a Reddit AMA, Kilmer said Frankenheimer was "desperate for a comeback and blamed me for the films failure," which he said didn't make sense because the film was still bad after his death scene. Amazing logic there, Iceman.

Kevin Costner

As is the case with The Island of Dr. Moreau, the production problems that plagued Waterworld were matched only by the bickering between the film's director, Kevin Reynolds, and star, Kevin Costner. Though they were frequent collaborators, having worked together on Dances with Wolves and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Costner and Reynolds' working relationship broke down under what Reynolds later described in a 2008 Sunday Times interview as incredible pressure due to the fact that it was "the most expensive [film] ever made." Though he did insist that they've repaired the relationship now that they're "older and wiser," and having come to the realization that "life is too short."

Reynolds was less diplomatic years earlier, around the time of the film's 1995 premiere, when he told EW, "In the future Costner should only appear in pictures he directs himself. That way he can always be working with his favorite actor and his favorite director." Zing! Costner, also speaking to EW in January of 2012, seemed to have evolved his perspective on the feud over time. He said, "We had differences. It happens, especially when the stakes are as high as they were with Waterworld. But out of fire comes steel. And I've always had a real belief in him as a director." In fact, Costner was speaking with the press at that time to promote his well-received miniseries, Hatfields & McCoys, which Watson directed, providing definitive proof that all of their burying-the-hatchet talk wasn't just Hollywood lip service.

Burt Reynolds

Many of these on-set altercations were undoubtedly tense and uncomfortable, but the only one on this list that ever ended in physical violence is thanks to Burt Reynolds and his well-known penchant for beating the crap out of colleagues he disagrees with. In a New York Times Magazine profile of the rough-and-tumble star, Reynolds is said to have thrown the director of Riverboat, his first TV show, into the water, as well as "'sailed' producer Joel Silver out of his trailer." He even admits that his "costliest fight" happened when he "punched out" Heat director, Dick Richards, after Richards "tapped Reynolds on the chest."

Post-slugfest, Richards left the set of Heat and sued Reynolds for $25 million dollars. Amazingly, Richards was somehow persuaded to come back to the film, only to later fall from a camera crane and have to be hospitalized. And to add insult to literal injuries, that lawsuit Richards filed didn't exactly turn out as planned either. "I spent $500,000 for that punch," Reynolds told The Times, revealing a substantially downgraded settlement from what Richards originally sought. Reynolds also joked, "If I hit a guy, it's certain that he will run a studio or become a huge director." We're not sure Dick Richards would agree with that assessment.

Burt Lancaster

As is the case with many of these scenarios, creative differences were said to be at the heart of star, Burt Lancaster, and director, Arthur Penn's fallout on the set of the WWII drama, The Train. According to TCM, Lancaster, who was also producing the film, felt that "Penn was neglecting the story's potential for action and suspense." But that's putting a shiny veneer on what, according to biographer Kate Buford, was actually an ego play on the part of Lancaster.

In her book, Burt Lancaster: An American Life, Buford interviews Walter Bernstein, the screenwriter who wrote The Train, and who was also present when Penn was unceremoniously kicked to the curb after the first day of shooting and replaced with John Frankenheimer. Bernstein tells Buford he was "appalled at what he felt was deeply unfair," and also remembers Lancaster saying, "Frankenheimer is a bit of a whore, but he'll do what I want."

Years later, in an interview with Bright Lights Film, Penn seems to confirm this characterization of both Lancaster and Frankenheimer when he referrs his firing as "a simple, very bad piece of nonsense that Burt Lancaster pulled." Penn claims that for "economic" reasons, Lancaster and Frankenheimer schemed behind his back to replace him all along, which Frankenheimer later acknowledged to Penn along with an admission that he was "an alcoholic during those years, and completely under the sway of Lancaster." Yeesh. What is the deal with Hollywood stars named Burt?

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson and Erich von Stroheim were giants of the silent film world. So, when they teamed up for Queen Kelly in 1928, which Senses of Cinema claims was "to be [director Stroheim's] masterpiece," the expectations were high. But Stroheim also had a reputation for eccentricity and pushing the envelope of good taste. So, he misrepresented the film's controversial nature when pitching it to Swanson and her producing partner and then-paramour, Joseph P. Kennedy — Yes, JFK's old man.

Anyway, after it became clear that Stroheim was making a scandalous and provocative film that she never agreed to — by failing to cut a brothel scene, and allegedly instructing a co-star to "drool on her hand" in another — Swanson complained to Kennedy and had Stroheim terminated. Swanson eventually finished the film, but in protest, Stroheim blocked its release in the U.S. for decades until after the two reunited for their classic roles in Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard. In a genius casting move, Stroheim played Max Von Mayerling, the butler to Swanson's Norma Desmond, a washed-up silent film star. Both would receive Oscar nominations for their roles, and Queen Kelly would eventually get a U.S. release and become a cult classic. Now that sounds like a Hollywood ending.