Secrets The NFL Tried To Hide

Few professional sports hold the same power as the NFL. In the prime of football season, there are games on Monday, Thursday, and Sunday -– plus Saturday, if you include the playoffs. There are dedicated fans who can tailgate for hours outside the stadium, even in freezing weather or worse, like the Kansas City Chiefs supporters, per CNN. Some historic franchises have been deeply connected with fans since the beginning, like the Green Bay Packers, who are the only publicly owned team, starting in 1923. The league also welcomed an entirely new aspect to the game in the 1960s with the introduction of fantasy football –- creating a hypothetical team where players earn points based on an NFL player's performance. By 2017, over 30 million Americans played in fantasy football leagues, via CBS.

But outside of the gridiron and behind the cameras is sometimes a much darker reality. Even listening to players that made millions as professional sports stars can reveal that life in the NFL isn't perfect. "I bet if you talked to 100 players, I bet you 85 to 90 of them are going to say they hate the N.F.L. I just think that's sad," former star running back Eric Dickerson told The New York Times. In his opinion, "The N.F.L. is another no-good entity." Throughout the years, the organization's issues have included questionable policies, inaction, exploitation, and generally shady tactics.

Are you ready for some controversy? These are the secrets the NFL tried to hide.

Players have a ton of health issues

Certain moments in the NFL stay with fans for generations, like the best plays ever in the league. But the game also has long-lasting effects on its players, especially when it comes to health. One study showed that former football players in the NFL die at a faster rate than their counterparts in professional baseball. Due to cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative illnesses, "on average, the football players died 7 years earlier than MLB players," per Science. Even worse, players in earlier generations often lacked programs to assist with their well-being. "When we came up in the league, we had no health care," former NFL running back Eric Dickerson explained to The New York Times.

Another common health issue is chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E. Boston University found C.T.E. in the brains of 99 percent of NFL players who participated in a study. "The data suggest that there is very likely a relationship between exposure to football and risk of developing the disease," explained the lead author on the study. The university also discovered that due to the high physical impact of football, the risk of developing C.T.E. doubled after only 2.6 years of playing the sport. Of the many players found with C.T.E., several committed suicide, including Aaron Hernandez, who was convicted for murder in 2015. After his death in 2017, examiners found the C.T.E. in 27-year-old was "the most severe case they had ever seen in someone of Aaron's age," The New York Times reported.

Harassment toward women in the league

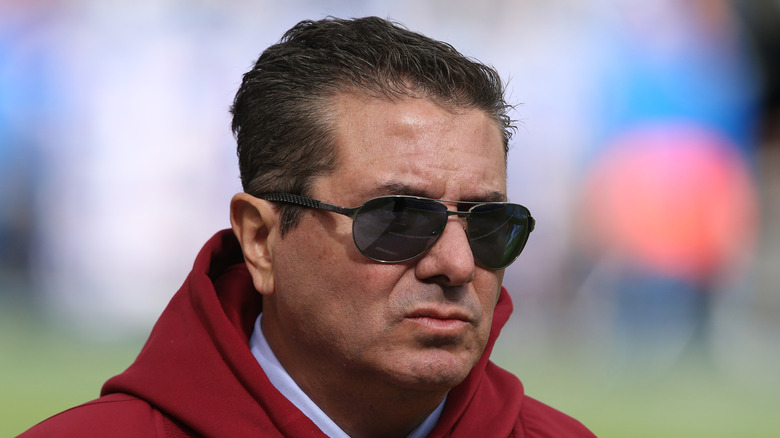

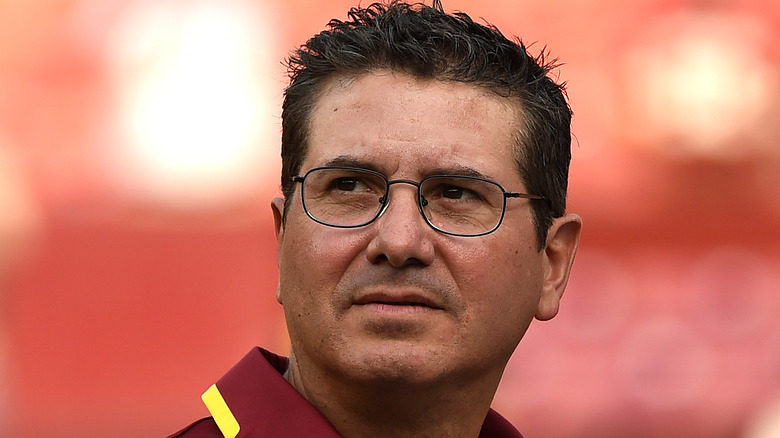

In 2020, 15 women who were former employees of The Washington Football Team spoke out to The Washington Post and claimed "they were sexually harassed during their time at the club." While fans were cheering on the team, these women said they dealt with "frequent sexual harassment and verbal abuse." According to the allegations that took place between 2006 and 2019, mostly under team owner Daniel Snyder, many of the top executives ignored any complaints of wrongdoing.

Snyder denied many of the claims and hired a law firm to internally investigate the situation. After people questioned the legitimacy of Snyder choosing the law firm, the NFL took over the investigation. Meanwhile, lawyers representing the women in the investigation challenged the NFL to "publicly commit to taking action to remove Snyder as the majority owner," The New York Times reported.

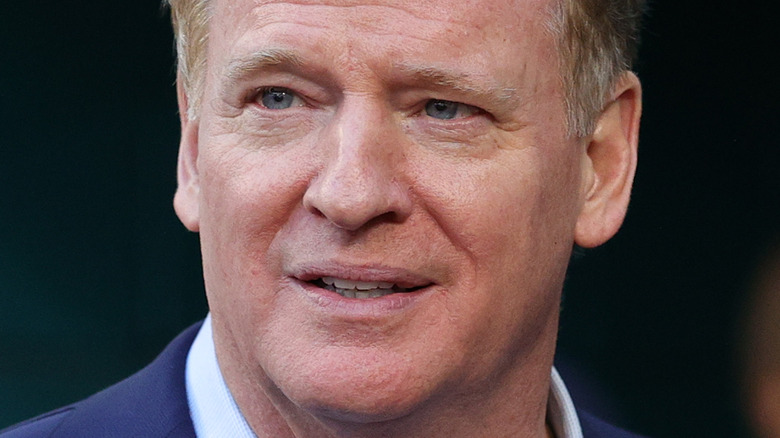

In the end, Roger Goodell, the NFL's commissioner, "fined the franchise a record $10 million and ordered Snyder to stay away from the team's facilities for several months," per The New York Times. But Goodell never released the results of the investigation to the public, "despite calls to do so by lawyers for some of the women who brought accusations and by members of Congress." Plus, Snyder allegedly tried to intervene when the NFL took over the investigation, even sending private investigators to intimidate people involved in the case, The Washington Post reported. As of 2022, Snyder was still the owner of The Washington Football Team.

The truth behind Ray Rice

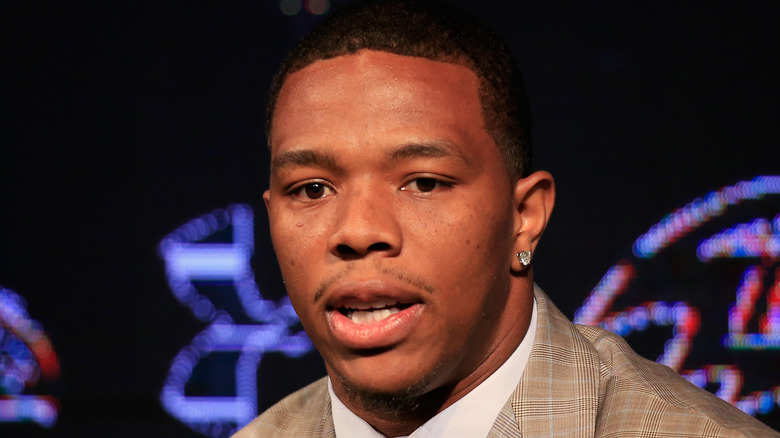

Ray Rice, a former running back for the Baltimore Ravens, became the subject of one of the biggest scandals in NFL history. In 2014, a video showed Rice dragging his fiancée, who appeared unconscious, out of an elevator in Atlantic City. Rice was accused of assault, and as a result, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell suspended the player for two games. Goodell said of the seemingly light punishment, "He's been accountable for his actions. He recognizes he made a horrible mistake, that it is unacceptable, by his standards and by our standards," per The New York Times.

Advocacy groups and others were outraged by Goodell's actions and claimed domestic violence was a bigger problem in the NFL. One of the groups said the league was "perpetuating a culture that tolerates violence against women." Soon after, TMZ released a bombshell video from inside the elevator. Rice was shown "delivering a vicious punch to his fiancée's face, knocking her out cold." The Ravens cut Rice from the team, and it was the end of his football career, History recapped.

The NFL claimed it didn't see footage from inside the elevator until TMZ released the video and kept details of its investigation private. Later, news broke that TMZ paid $91,000 to obtain the brutal footage of Rice, USA Today reported. Plus, the NFL reportedly received the video of Rice punching his fiancée in April of 2014, months before the TMZ release, per the Associated Press.

Players go big then go broke

For those who think that becoming a professional football player in the NFL is the golden ticket to lifelong wealth, the reality is far different. In fact, many players go from insane wealth on paper and living the life of luxury to practically nothing. It's almost hard to believe that only two years after retiring from the game, "78% of former NFL players have gone bankrupt or are under financial stress because of joblessness or divorce," per Sports Illustrated.

There are multiple reasons that players can go from counting bills to counting nothing. The biggest includes players buying into private investment deals that don't return big financial gains as promised. "Chronic over allocation into real estate and bad private equity is the Number 1 problem [for athletes] in terms of a financial meltdown," a wealth management professional explained.

In addition to new people entering the lives of players and asking for money, NFL stars often have no experience in budgeting and finance. Plus, some say that the league doesn't provide enough education to help its players avoid financial ruin. "They don't want to help you, they don't give a damn about you," former player Eric Dickerson told The New York Times about the NFL. To avoid financial stress after retirement, players need to take it upon themselves to set budgets –- like Ryan Broyles of the Detroit Lions, who lived off a $60,000-a-year budget for him and his wife, ESPN reported.

Messing with hometown fans

Many fans grew up watching their favorite NFL teams from a young age, with stories and jerseys passed down through generations. Some cities, including Buffalo, New York, have had an NFL team in town since the 1920s. Sadly, other cities saw their teams rise to greatness before leaving town. The Rams franchise first started out in Cleveland in 1937, and after finally winning the NFL championship, its owner moved the team "to Los Angeles for the 1946 season," as recapped by the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The team stayed in California for decades before relocating back to the Midwest in 1995, this time in St. Louis. After an awful 1998 season when the team went 4-12, the Rams returned with a vengeance. Helmed by quarterback "Kurt Warner, who previously worked at a grocery store before making it in the NFL," the team went 13-3 in the next season and won the Super Bowl in 2000, per the Rams Wire. It was the first and last championship for the St. Louis Rams.

For the 2016 season, the franchise returned to Los Angeles. While fans on the West Coast were happy for a new team, behind the scenes was a legal mess. The St. Louis Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority brought a lawsuit against the move, alleging "that the league broke its own relocation guidelines, misled the public on its plans to leave the city and cost the city millions in revenue," ESPN reported.

There are shady team owners

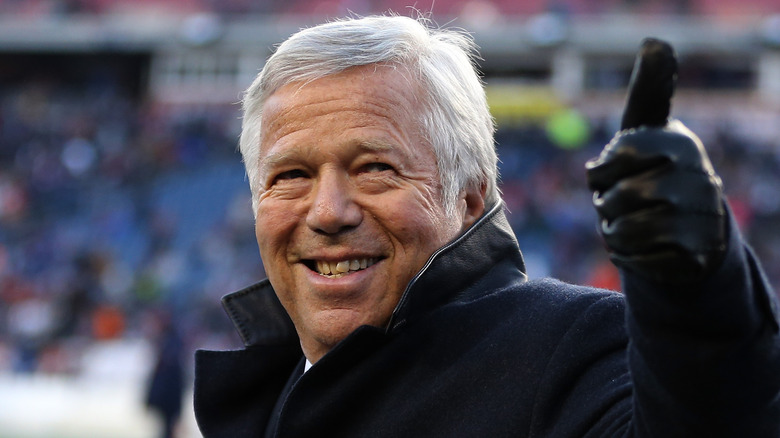

Owning an NFL team is a dream for some, and for those who already own one, it can be a lucrative investment. As of 2021, David Tepper, who owned the Carolina Panthers, was the richest owner with an estimated net worth of $14.5 billion. Other billionaire owners included Jerry Jones of the Dallas Cowboys, Stan Kroenke of the Los Angeles Rams, and Robert Kraft of the New England Patriots, per Forbes.

Despite the massive wealth of many of these men, several team owners have been downright shady. For example, Tepper purchased the Panthers from franchise founder Jerry Richardson, whom the NFL investigated "for sexual and racial workplace misconduct," ESPN recapped. According to sources, four ex-employees with the Panthers were paid large settlements as a result of Richardson's "sexually suggestive language and behavior," Sports Illustrated reported. The NFL fined Richardson $2.75 million in 2018 but avoided providing details of the allegations, per The New York Times. Plus, Richardson collected $2.2 billion from selling his team.

The following year, Kraft became the next owner to find himself in hot water after he was arrested in a prostitution sting. In January of 2019, the Patriots owner was getting a massage in a Florida spa where he "and other men were filmed allegedly paying for sex," The New York Times reported. Ultimately, the video evidence was dismissed and charges against Kraft were dropped after "several judges chastised the police for the way they procured warrants to install hidden video cameras" at the spa.

How much money the league makes

It can be shocking to learn how much money some NFL players make. For example, in 2020, Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes signed the biggest NFL contract in the organization's history for 10 years and $450 million, Forbes reported. But these figures are nothing compared to what the league makes for itself. Even with hardly any fans in attendance in 2020 because of COVID-19 restrictions, revenues were in the $12 billion range, per Sports Business Journal. This was a 25% drop from the previous year, which brought in $16 billion. If the 2020 season had gone as planned, revenues could have been around the $16.5 billion that was projected.

Most of the losses were from local revenues, which the teams earned individually. The league revenues, which are split evenly among all the teams, were $9.5 billion in 2019 and didn't decrease as much because the league still earned all of its media payments. In fact, half of the money that the NFL makes comes from TV sponsorships. The three major networks that broadcast the games, NBC, CBS, and Fox, signed a contract "to pay the NFL $39.6 billion between the 2014 and 2022 seasons," Investopedia recapped.

Even more surprising was the extra money the league was making thanks to a long-standing exemption. Starting in 1942, the NFL was tax-exempt. It was only in 2015 that the league finally gave up the status "in response to mounting criticism for its quickly growing revenue."

Advanced forms of cheating

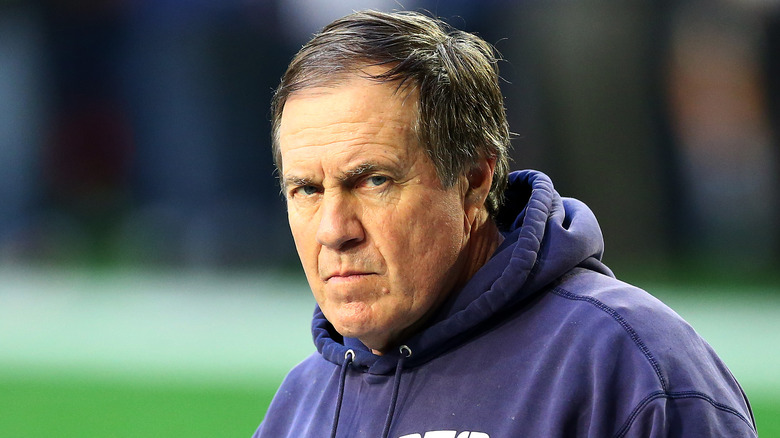

Sounding more like a political scandal than an NFL controversy, "Spygate" rocked the league in 2007. A video assistant for the New England Patriots was caught filming the New York Jets' defensive signals -– gestures by coaches to players for strategy. The NFL fined the Patriots' head coach $500,000 and another $250,000 to the team because "it was believed the Patriots' coaches were using the film to make halftime adjustments," ESPN recapped. Bill Belichick, the coach for the Patriots, said, "I respect the integrity of the game and always have and always will." According to the coach, "the practice was immediately stopped, and we're not doing it."

Even though the Patriots also lost a first-round draft pick the following season, people still felt the NFL needed to do more. Specifically, the league never released footage of the "Spygate" video and instead destroyed the tapes and notes. "I have nothing to hide," Goodell said of his decision, per ESPN. "I think it was the right thing to do," he added.

Years later, the Patriots were involved in another cheating scandal. This time, legendary quarterback Tom Brady was at the center of a controversy dubbed "Deflategate." Opponents claimed Brady used intentionally deflated footballs while playing to help improve his accuracy. As a result, the NFL spent over "$22 million over the course of two years to investigate, litigate and discipline Brady and the organization," ESPN explained. The quarterback was suspended for four games.

Preventing fans from watching the game

Any fan who used to watch NFL football always knew there was a possibility their team wouldn't appear on TV that week –- an occurrence called a blackout. In the 1970s, the NFL instituted a policy that stated "a game must be blacked out on local TV markets in the event that fewer than 85 percent of available seats have been sold 72 hours prior to kickoff," Sports Illustrated recapped.

The FCC had its own blackout rules from the mid-'70s to 2014, "which prohibited cable and satellite operators from airing any sports event that was blacked out on a local broadcast station." For example, the Buffalo Bills in 2013 were at risk of having a home game blacked out if they couldn't sell 7,000 tickets, CBS reported. Despite providing $15 discounts, the NFL stepped in and gave "a 24-hour extension" to the Buffalo Bills to sell 5,300 tickets. The team's owner swooped in and bought the remaining tickets himself. He even used the same tactic a month later. But that December, the team finally had its first blackout, The Buffalo News reported.

Finally, in 2015, the NFL suspended its blackout rule. Many thought that ending the practice was just a savvy business decision on the league's part. "This no-lose public relations move attempts to create a singular positive vibe," a sports economist told CNBC. In addition, the NFL allegedly took the action to get "ahead of lawmakers and regulators" and make a favorable impression on fans.

The two words people can't say

If you've ever seen an advertisement on TV or in person for "The Big Game," it is likely referring to the Super Bowl. The reason for this common practice is because "if you don't pay a fee to the NFL, you can't use the name Super Bowl in ads," the New York Post explained. Advertisers who run Super Bowl commercials, which cost about $5.5 million for 30-seconds in 2020, per The Wall Street Journal, earn the right to use the official name.

Additionally, companies that "commit to multi-year deals that permit them to tack the Super Bowl name and logo onto their products." For example, "Anheuser-Busch spends around $250 million a year to be the only alcohol company allowed to advertise nationally during the game, and to use the various Super Bowl trademarks on its products," per Vox. The NFL first trademarked the phrase Super Bowl in 1969 and later added the phrase "Super Sunday" to its list of trademarks.

For those in violation, no matter how small, the NFL often notices. Like when the league threatened legal action against a pastor in Indiana for hosting a church-sponsored party to watch the Super Bowl with a $3 admission fee. The NFL claimed other churches were breaking its copyright laws by charging people to view the game, ABC News reported. The NFL also used to forbid viewing parties on TV screens over 55 inches, but after receiving backlash, the league ultimately exempted churches from the rule, per The Washington Post.

The Colin Kaepernick story

In a 2016 pre-season game between the San Diego Chargers and the San Francisco 49ers, quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a defiant stance. Or rather, the 49ers QB kneeled. During the national anthem, Kaepernick and teammate Eric Reid used the action as a form of protest. Before the game, Kaepernick consulted with Nate Boyer, a former member of the United States Army Special Forces, to see "if there was a way he could protest racial inequality and police brutality in the United States without offending people in the military," NBC reported. Boyer allegedly told Kaepernick that kneeling seemed appropriate.

While the move was celebrated by many as a brave statement, it started a wave of controversy involving politics and professional sports. The quarterback later explained that he did this action in support of America and racial equality. "I want to help make America better. I think having these conversations helps everybody have a better understanding of where everybody is coming from," he said.

In a statement to AP, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said about Kaepernick, "I don't necessarily agree with what he is doing." He stated that while the NFL supports its players, "On the other hand, we believe very strongly in patriotism in the NFL. I personally believe very strongly in that." Meanwhile, then-president Barack Obama voiced his support for the football player, NBC Sports reported. After the season, no NFL team would sign Kaepernick, The Washington Post recapped. As of 2022, the former quarterback still was unsigned.

The controversial team name in Washington

One of the earliest professional football teams on the East Coast was the Boston Braves, which changed its name to the Boston Redskins in 1933. The team's owner, George Preston Marshall, said at the time that he changed the name to avoid confusion with the baseball team of the same name. The football team then moved to the nation's capital in 1937 and became the Washington Redskins.

As if the name wasn't offensive enough, Marshall's wife wrote the team's fight song, which included controversial lyrics. And It wasn't until 1961 that Marshall, "under pressure from the Kennedy White House, [became] the last NFL owner to integrate his team," The Washington Post recapped. Then, in 1972, Native American leaders asked the team's president to choose a new team name. This began a contentious back and forth for decades involving trademark registrations, presidential comments, and increased pressure to change the team name. But when asked if he would consider changing the team name in 2013, owner Dan Snyder was adamant that he would continue resisting the critics. "We'll never change the name. It's that simple. NEVER -– you can use caps," he told USA Today.

Never say never because the team released a statement in 2020 that said, "We will be retiring the Redskins name and logo." Thanks in part to fans and corporate sponsors asking for a change, the team became known as the Washington Football Team, until February 2022, when they chose the moniker the Commanders.

Players enhancing their performance

One of the long-standing tarnishes on professional baseball is the use of steroids by its star players. Starting in the late '80s and until the MLB started testing for performance-enhancing drugs in 2003, many players allegedly used the drugs to help improve their hitting power, per ESPN.

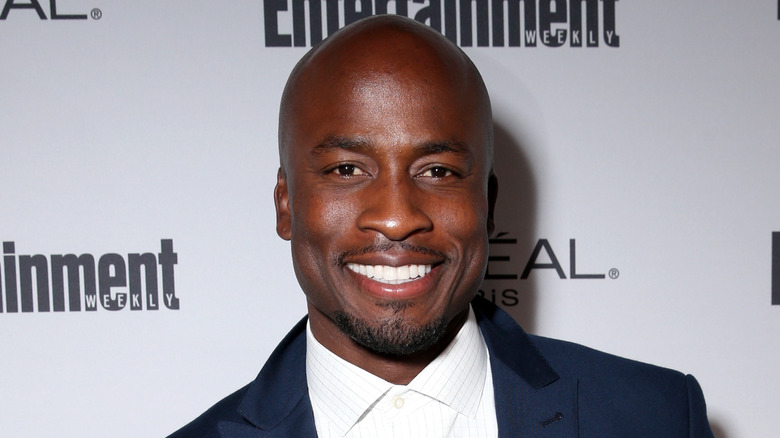

The NFL was also a common place for athletes to look for a competitive advantage with performance-enhancing drugs. Former player Akbar Gbajabiamila said a popular drug of choice in the NFL during the early aughts was Toradol, often referred to as "T-train." Though Toradol is a nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drug, "I felt like it gave me an edge, but in reality I was just on an even playing field because this was customary in every locker room around the league," he told the NFL.

In 2015, another player told the Bleacher Report that while steroids were less widely used, "HGH is the big problem. For the past four or five years, the league has been almost overrun by HGH." Allegedly, the NFL's testing procedures weren't robust enough to catch players using the human growth hormone. In fact, the publication estimated that between 10 and 40 percent of NFL players at the time used HGH. News network Al Jazeera suggested in a documentary that famous quarterback Peyton Manning used HGH, The Washington Post recapped. The claims were never substantiated, and in 2021, Peyton Manning was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The less cheerful side for cheerleaders

Cheerleaders have long been a part of the football experience at all levels of the sport -– it's a great way to get fans excited about the action on the field. It even is practiced competitively, whether in fictional settings like "Bring It On" or following the Navarro College team on the docuseries "Cheer."

In the NFL, the role of cheerleader can be a highly coveted position. None more famous than the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders, a prestigious group that eventually became known for their iconic uniforms. As a former NFL cheerleader once said about the Cowboys cheerleaders, "When they walk in, you can just tell," per Vanity Fair. In fact, as of 2018, there were about 500 former NFL cheerleaders. But the truth behind the cheer pompoms sadly is uglier. Some teams allegedly forced their cheerleaders "to pose topless," while other cheerleaders claimed they earned less than minimum wage and were body-shamed.

Cheerleaders were also included in the downfall of former coach and commentator Jon Gruden. He was in the spotlight in 2021 after some of his emails were leaked, which "used misogynistic and homophobic language to disparage people," per The New York Times. More than just his awful words, Gruden possessed explicit "photos of women wearing only bikini bottoms," two of whom were cheerleaders in Washington. Previously, the league investigated another email by Gruden in 2011 that contained racist language. But it was only after The New York Times released the misogynistic emails that Gruden immediately resigned.

Encouraging dirty plays

In the 2009 NFL season, the New Orleans Saints reached the sport's pinnacle and won the Super Bowl. But behind the scenes, some coaches and players began a disturbing practice. Starting that season and through 2011, the Saints "operated a bounty system in which players were paid bonuses for, among other things, hard hits and deliberately injuring opposing players," ESPN reported. An NFL investigation found that over 20 players actively participated in pooling money for the bounty and that while he wasn't directly involved, head coach Sean Payton knew about the operation and let it continue. As a result, Payton was suspended from the league for a year without pay, and the team was fined $500,000 in addition to losing draft picks, the NFL detailed.

On the "Going Deep" podcast, former Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker James Harrison said he was once paid money for a monster hit in 2010. He claimed his coach at the time, Mike Tomlin, handed him an envelope with a reward inside. The NFL fined Harrison $50,000 for the concussion-inducing hit on wide receiver Mohamed Massaquoi. After hearing the story, Steelers president Art Rooney II said, "I am very certain nothing like this ever happened," per the NFL. He added, "There is simply no basis for believing anything like this." Payton told 105.7 The Fan that the NFL would likely never investigate Harrison's claim and called his previous investigation a "sham." The coach said of his own experience, nicknamed Bountygate, "Honestly, it was something I'll never truly get over."