The Shady Side Of The Grammys

The Grammy Awards market themselves as "music's biggest night," and they might be right. Held annually early in the year by the Recording Academy, they're a celebration of the best and brightest of the previous year's music, with awards handed out in virtually every genre of music with the biggest ones of the night going to Album of the Year, Record of the Year, Song of the Year, and Best New Artist. The show itself features some trophy presentations along with lots of music performances and collaborations, so it's certainly something to see for big music fans.

However, the Grammys are also very much an extension of the rich and powerful American music industry, and they're as much about putting on a show and advancing the careers of certain singers and bands as they are about rewarding artistic achievement. There's a lot of politics, marketing, and PR machinations involved with presenting music's biggest night each year, as has been done since the late 1950s. Here are some of the seedier, scandalous, and embarrassing elements of the Grammy Awards, past, present, and future.

The slightly sleazy origins of the Grammy Awards

Now regarded as the highest honor for a professional commercial musician, the equivalent of an Emmy for a TV actor, and Oscar for a filmmaker, or a Tony Award for a Broadway star, the Grammy Award is the youngest of the four entertainment trophies that comprised the fated "EGOT." Almost called the Eddie, the first Grammy Awards (short for "gramophone," the early and now completely obsolete way of playing recorded music), were handed out in 1959. While raucous rock n' roll is the type of music most associated with the 1950s, the initial Grammy ceremony didn't honor such youthful sounds at all, awarding Album of the Year to film and TV composer Henry Mancini's The Music from Peter Gunn (over two Frank Sinatra LPs).

But then, the Grammys weren't necessarily started to honor the most artistically provocative music of the year. The awards were an outgrowth of the vaunted Walk of Fame in Hollywood. In 1957, the city's Chamber of Commerce decided to honor all media entertainers with a plaque bearing their name, deciding that recording artists would be worthy of inclusion if they had sold at least a million singles or 250,000 albums. That's when organizers realized that some of the most important musicians, in their opinions, hadn't reached those sales benchmarks. And so, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences was created, specifically, to hand out annual awards to the musicians it decided it wanted to honor.

Hold up, why did Beyoncé lose to Adele?

The Grammy Awards tend to bestow honors on popular artists, but not necessarily the most progressive or important ones. Case in point: huge-voiced torch singer and songwriter Adele has won 15 Grammys. Adele's winning ballads like "Rolling in the Deep" and "Hello," and the LPs 21 and 25 earned a lot of radio play and moved millions of copies, respectively, but Adele isn't widely heralded as a game-changing artist or the voice of a generation in the way that Beyoncé is.

During her acceptance speech when 25 won Album of the Year, Adele voiced confusion over losing to Beyoncé's Lemonade, which Rolling Stone had just named the second best album of 2016. "My artist of my life is Beyoncé ... the Lemonade album was just so monumental," the singer said.

The reason Adele beat Beyoncé, suggested by CNN, was racially motivated. Lemonade was an album about Black identity, and older Grammy voters didn't care for it or relate to it. CNN also mentioned that only a few African-American artists had taken home the Album of the Year award in the past two decades — Lauryn Hill, Outkast, Ray Charles, and Herbie Hancock. Slate music journalist Chris Molanphy (among others) figured that Grammy organizers elevated the Urban Contemporary category, which Beyoncé was expected to win and did, as a PR move. "I'm convinced the Urban Contemporary award was televised this year cuz this is the last Grammy Bey's taking tonight, sadly," Molanphy tweeted.

The Grammys love vintage musical acts

It's not just the white acts that tend to receive preferential treatment on Grammy voter ballots, allegedly, but it's older acts, too. Over the years, and over and over again, the Recording Academy's contingent of white and aged Grammy deciders have shown a distinct bias toward singers and bands with familiar names that have been around for years and built up goodwill, handing them awards for their later, less-than-classic works over progressive, groundbreaking work by newer artists whose music may be strange and unfamiliar to them (via Billboard).

For example, the 1989 Grammys featured the first appearance of a long-overdue award for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance. While definitive metal band Metallica was nominated for ...And Justice for All, the Grammy went to Crest of a Knave by Jethro Tull, a prog-rock band far off its early '70s commercial and artistic peak, led by frontman Ian Anderson who played the flute, the most un-metal of instruments. When presenter Alice Cooper opened the envelope and saw "Jethro Tull," he thought he'd received a prank or prop envelope, and some members of the audience laughed.

And then there's Steely Dan, winners of the Grammys' Album of the Year. But they didn't win for '70s-era LPs like Aja — the duo got it for Two Against Nature in 2001, defeating envelope-pushing youthful acts like Radiohead (Kid A), Beck (Midnite Vultures), and Eminem (The Marshall Mathers LP).

Milli Vanilli fooled the Grammys

The Grammy Awards operate under a slew of eligibility rules and requirements, ensuring that the plaudits artists receive are as credible and industry-approved as possible. According to Stereogum, only once has an awarded Grammy been revoked, and it was one of the major ones, the end result of one of the biggest scandals in pop music history.

At the 1990 Grammy Awards, European dance-pop duo Milli Vanilli won in the Best New Artist category, defeating Neneh Cherry, Soul II Soul, Tone Loc, and Indigo Girls. That was a logical pick, as Milli Vanilli had enjoyed an extremely successful 1989 and was looking good in 1990, too — three of its first four singles ("Blame it on the Rain," "Girl I'm Gonna Miss You," and "Baby Don't Forget My Number") all hit #1 on the pop chart, and the week they won Best New Artist, "All or Nothing" was in the Billboard top 5.

Within a few months, it was all over. According to the Grammys website, Milli Vanilli producer Frank Farian revealed that singers Fab Morvan and Rob Pilatus were fronts, handsome guys hired to be the face of the group but who hadn't actually sung a note of their recordings. Morvan and Pilatus subsequently returned their Grammys.

The Grammys can't define what a 'new artist' is

The Grammy for Best New Artist is one of the most important ones given out each year, but it doesn't help that the rules that govern who can be nominated for and receive it are seemingly and confusingly arbitrary. Country singer Shelby Lynne took home the award in 2001, a good ten years after the Academy of Country Music Awards named her New Female Vocalist of the year back in 1990. In 1999, Lauryn Hill was named Best New Artist, even though she'd been a member of the prominent and popular hip-hop collective, the Fugees, for years.

The Grammys are quite flexible with the definition of "new artist," and yet it wouldn't budge for Lady Gaga. In 2010, she was deemed ineligible for Best New Artist because just before she broke out big, one of her early singles was nominated in the Best Dance Recording category. The resulting controversy led the Recording Academy to change its Best New Artist rules, allowing eligibility for an act if "an artist/group is nominated (but does not win) for the release of a single or as a featured artist or collaborator on a compilation or other artist's album before the artist/group has released an entire album (and becomes eligible in this category for the first time)" (via Entertainment Weekly).

Nevertheless, in 2012, indie outfit Bon Iver won Best New Artist in 2012, despite having released its debut album in 2008.

Bob Dylan got Soy Bombed

One would think that with hundreds of important people in attendance, the Grammy Awards would have a sophisticated security system in place, thus preventing interlopers from getting too close to the talent. And maybe they do, especially after the strange madness that somehow went down at the 1998 ceremony.

Twice that night, people somehow rushed the stage, got right next to stars, and made it onto the TV broadcast before being whisked away by security. Bob Dylan, who'd win three Grammys that night, including Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind, gave an intimate performance of his song "Love Sick," surrounded by a small group of young people paid $200 each to sit there and look on adoringly. Per The Hollywood Reporter, suddenly, one of those extras, performance artist Michael Portnoy, jumped up and started flailing and gyrating next to a nonplussed Dylan, his shirt off and the words "Soy Bomb" painted on his chest until a show employee escorted him off the stage and kicked him out of the venue.

ODB lost an award and rushed the stage in protest

Michael "Soy Bomb" Portnoy would have been the most-talked-about person of the night during the 1998 Grammy Awards were it not for Ol' Dirty Bastard. According to MTV, just before announced winner Shawn Colvin could give her acceptance speech for Song of the Year (for "Sunny Came Home"), the Wu-Tang Clan rapper jumped onto the stage, kissed presenter Erykah Badu, and grabbed the microphone.

"I went and bought me an outfit today that cost me a lot of money, because I figured Wu-Tang was gonna win," he said, referring to his group's loss in the Best Rap Album category to Puff Daddy. "I don't know how you all see it, but when it comes to the children, Wu-Tang is for the children," he went on. "Puffy is good, but Wu-Tang is the best. I want you all to know that this is ODB, and I love you all, peace." Once more, Grammy personnel had to help somebody hastily make an exit from the stage.

Anyone with $100 and an album can win a Grammy

Securing a Grammy nomination is a milestone achievement for any artist. But they can also be engineered, suggesting that the Grammys aren't as pure and artistically-driven as its organizers would like the world to believe. In December 2012, nominations for the 55th annual Grammy Awards were announced, and the Best Dance Recording category was particularly stacked, featuring entries from Skrillex, Avicii, Calvin Harris, and Al Walser (via NPR). Not familiar with Walser or his nominated song, "I Can't Live Without You"? Few were.

Per Spin, at the time of his nomination, his Facebook page had just over 1,400 likes, and his YouTube videos had been viewed about 7,000 times. Walser is a producer and DJ from Liechtenstein as well as the author of Musicians Make it Big. The book is full of tips and tricks to exploit the music industry's back channels, which is how he gamed himself a Grammy nom. He used Grammy365, a private social network for Grammy voters, and sent out about 7,000 messages asking people to listen to (and vote for) "I Can't Live Without You," and it worked. (He still lost to Skrillex, however.)

In 2012, folk singer Linda Chorney also used Grammy365 to get herself a Grammy nomination for Best Americana Album for Emotional Jukebox. She paid the $100 fee to join the site, and, like Walser, campaigned to voters, simply asking them to listen to her music. They did, and subsequently nominated her, however media reports that she'd never actually sold any of her music put a damper on her big moment. In reality, Chorney is said to have sold some "10,000 albums" (via The Hollywood Reporter), albeit independently, which means those sales didn't register on certain industry watchlists. Public outcry aside, perhaps the Grammys would do well to clarify exactly how the nomination process works, in an effort to avoid such unnecessary controversy.

That time when a bunch of major rap artists boycotted the Grammys

According to Vox, in the mid-1980s, the Grammy Awards had a reputation of being out of touch with quality contemporary music and changing times. In 1989, after about a decade into its life, rap and hip-hop received its own Grammy category. The nominees for the first Best Rap Performance Grammy: Salt-n-Pepa ("Push It"), LL Cool J ("Going Back to Cali"), Kool Moe Dee ("Wild Wild West"), J.J. Fad ("Supersonic"), and DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince ("Parents Just Don't Understand").

Per The Hollywood Reporter, at the time, the Recording Academy wasn't totally ready to embrace rap and decided that the awarding of the Best Rap Performance wouldn't be a part of the televised Grammy ceremony. "They said there wasn't enough time," DJ Jazzy Jeff told ET. "They televised 16 categories and from record sales, from the Billboard charts, from the overall public's view, there's no way you can tell me that out of 16 categories, that rap isn't in the top 16."

And so, DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince publicly boycotted the 1989 Grammy Awards. They were joined by fellow nominees LL Cool J (later a Grammys host) and Salt-N-Pepa, who said in a statement (via MTV), "If they don't want us, we don't want them."

Is the fix in?

In January 2020, the Recording Academy, the music industry organization that awards the Grammys, placed its chief executive, Deborah Dugan, on administrative leave just five months after she took the job, and mere days before the 2020 Grammy Awards show (via NBC News). According to Rolling Stone, it was after a senior member of the Academy lodged "a formal allegation of misconduct" against Dugan. Per NBC News, Dugan had also allegedly fostered a "toxic" workplace with a management style characterized as "abusive and bullying." After her suspension, Dugan filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, citing discrimination and claiming that she was punished because she'd registered concerns about other Academy employees to its Human Resources department in December 2019.

Along with allegations of gender discrimination and sexual harassment, Dugan took issue with the Grammy nominating process, citing "egregious conflicts of interest, improper self-dealing by board members, and voting irregularities." In other words, Dugan claimed, the Grammys were rigged. "If there are certain artists that the producer would like [to perform] on the [televised Grammy Awards] show, there are strong hints, influence, that might affect a select few in the nominating process," she said. Dugan said that Ariana Grande and Ed Sheeran were denied Song of the Year nominations in 2020 because powerful Grammy selectors had their own preferred artists in mind.

The Recording Academy denied everything, citing "rigorous and well-publicized protocols in place to ensure that voting is absolutely fair."

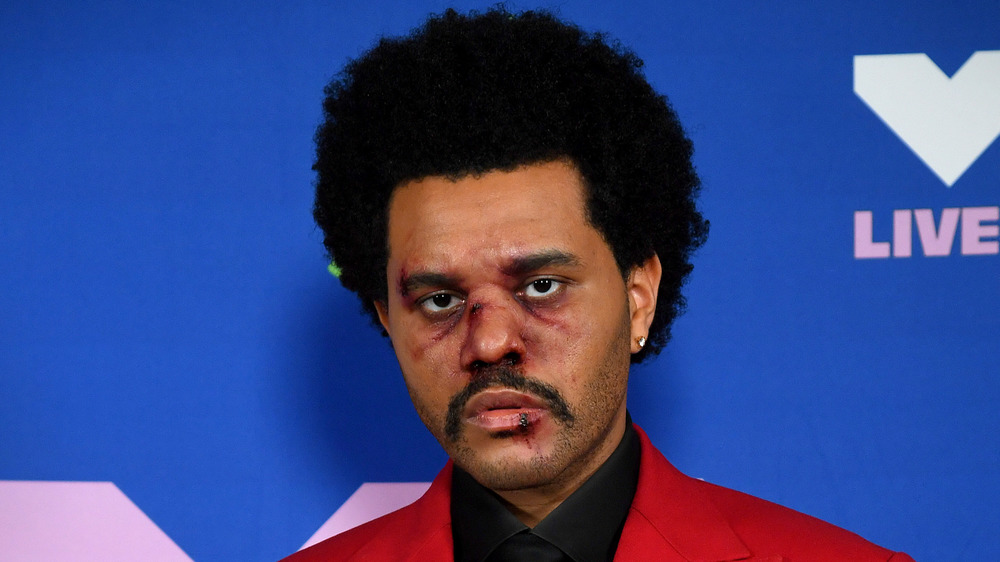

The Weeknd was completely snubbed

Every awards ceremony is going to feature some "snubs." There are only so many categories with so many slots in each — there's simply too much good music to include everyone who deserves a nomination, even after the Grammys expanded the number of slots in the major categories (Album of the Year, Song of the Year, Record of the Year, and Best. New Artist) from five to eight.

Genre-defying superstar The Weeknd was a virtual lock-in for multiple nominations at the 2021 ceremony, according to Grammy prognosticators. Vulture called him "too big to fail," and predicted he'd get nods in Album of the Year (for Blinding Lights) and in Record of the Year and Song of the Year for "Blinding Lights," which Billboard named the most successful song of 2020. GoldDerby agreed, making The Weeknd the odds-on favorite to win in all three huge Grammy categories.

It was shocking, then, when the nomination list was revealed, and The Weeknd didn't receive any recognition at all, in any category. The Weeknd registered his disappointment on Twitter, writing, "The Grammys remain corrupt. You owe me, my fans and the industry transparency." Drake agreed, writing on Instagram (via CNN), "I think we should stop allowing ourselves to be shocked every year by the disconnect between impactful music and these awards and just accept that what once was the highest form of recognition may no longer matter to the artists that exist now and the ones that come after."