Bizarre Things That Never Made Sense About The Amanda Knox Case

The case of Amanda Knox offers international intrigue at its finest. The nine-year ordeal, which has crossed oceans, spanned two trials, and started with the tragic death in Italy of 21-year-old British exchange student Meredith Kercher, has captivated the eyes of audiences worldwide like few murder cases ever have. Even with her innocence seemingly established, there's plenty about the case that cast suspicion on Knox, and more that just plain never made sense. Read on as we go over the stranger pieces of this tantalizing mystery.

An international incident

In case you don't recall all the details, Knox was accused (along with her boyfriend at the time, Raffaele Sollecito) of the savage murder of Ms. Kercher, her roommate and fellow exchange student. Kercher was from Britain; Knox from Seattle. When Kercher was found murdered in the house she shared with Knox and a handful of other roommates, suspicion fell upon the couple due to their proximity to the crime. Thanks to the evidence that was there (as well as some that wasn't), as well as Knox's strange behavior after the discovery of the grisly scene and in the aftermath, it's no surprise that she fell under the suspicion of Italian officials who were eager to solve the case.

Right up front, it's worth mentioning that in our view, she's convincingly innocent. Because of how the Italian justice system works, Knox and her co-defendant were put through two trials, convicted both times, and both times had the verdicts overturned by a higher court. If you ask us, two trials is enough—it'd be reasonable to fear that an overzealous prosecutor could try to haul her back for an endless series of trials, if not for the fact that Italy closed the case for good in early 2015.

Amanda's strange behavior

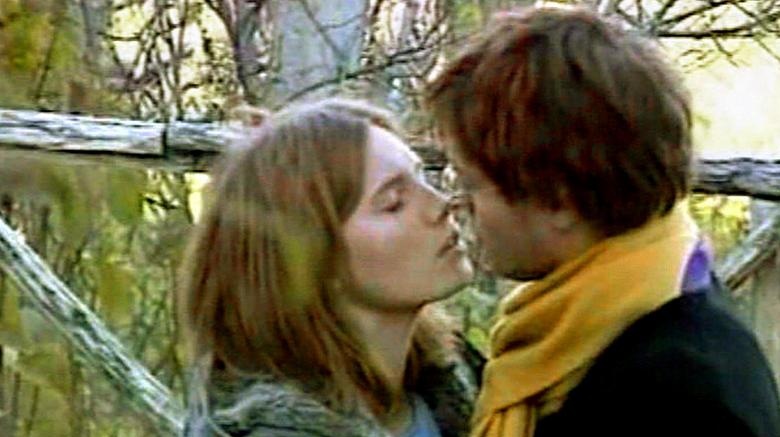

There were admittedly some reasons for the Italian police to be suspicious. A scary thing about criminal trials, and one of the scariest things about this case, is how much of what we think of as the truth turns on perception—and perceptions can be distorted, or simply not reflect reality. But in the aftermath of Kercher's murder, Knox and Sollecito made some critical mistakes. She adopted a relaxed attitude at the police station; seeking comfort from her boyfriend, her interactions with him were seen as amorous canoodling, inappropriate at best, suspicious at worst. Kisses that may have otherwise been seen as innocuous were distorted to present Knox as a manipulative, sex-crazed monster, which is shocking when you consider how relatively benign the pictures are. Still, not a good move from a PR perspective. Another one of Knox's mistakes? She's the only one among her roommates who didn't immediately lawyer up. Whether this was due to misplaced faith in the justice system or a naïve sense that her innocence was obvious, it was one mistake in an avalanche that very nearly cost Knox her freedom and her life.

Theories of devil worship

Cases of devil worship leading up to murder have been greatly exaggerated in the popular consciousness. Incidents such as these, which are almost never true, have nonetheless resulted in lives being ruined due to baseless accusations against people who are a little, well, weird—enough for it to seem just barely plausible that they worship Satan and savagely kill. It happened with the West Memphis Three in Arkansas, and it happened with Amanda Knox in Italy. Theories of devil worship in this case can get fairly unhinged, and it's difficult to believe that accusations this incendiary got any credibility in the public—the fact that they did is one of the scariest aspects of Knox's ordeal. It can be argued that the reasons why are cultural—Italy's relationship with occult thought and fabulist conspiracies is slightly different than America's, in a social sense—but a large degree of the responsibility for these theories comes down to one man: the prosecutor.

An overzealous prosecutor

The more we learn about the context of the Amanda Knox trial, the weirder things tend to get, and nothing is stranger, perhaps, than the scorch-the-earth tactics that Italian prosecutor Giuliano Mignini brought to the trial. For American audiences, the zeal with which Mignini attacked Knox blurred the lines between prosecution and persecution. He was primarily responsible for pressing the occult narrative on the case, alleging that Knox, Sollecito, and a third man conspired to kill Kercher as part of an occult-influenced sex game gone wrong. Un festino di giochi proibiti—"a party of forbidden games." This theory was later revealed to be based on nothing. The zealousness with which Mignini approached this case and others would eventually get him into trouble—he was convicted of corruption for abusing his office and tapping phones. Why he's so passionate about conspiracies and magic rituals that are considerably less than real remains a mystery.

A theory of three killers

The evidence, in retrospect, seems to sensibly point one way. Male footprints, no forced entry, a stabbing in the bedroom, a murder scene wiped clean. An obvious question gets raised—did Kercher bring her killer home with her? But this theory, simple and sensible though it may be, didn't get nearly as much traction as a narrative focused on conspiracy. Pressed most strongly by prosecutor Mignini, a theory emerged based on Masonic ritual and obscure occult traditions both real and imagined. Instead of a straightforward narrative of one killer, Mignini became obsessed with the notion that three people had killed Kercher together, despite a complete lack of evidence supporting his theory.

The guilt of Rudy Guede

The most shocking thing about the trials is that they went forward after someone else was already convicted of the murder.

Rudy Guede was convicted of the murder by an Italian court in 2008, which in a different universe would have been the end of this story. But the prosecutors became convinced—and Guede helped to spread the lie—that Knox and Sollecito were involved, despite the fact that there existed no records at the time of phone calls or texts ever being exchanged between Knox, Raffaele, and Guede. Simply put, they didn't know each other—and why this was ignored so enthusiastically is a mystery that endures to this day. Prosecutors continued to press the theory that he was the killer, plus Knox and Sollecito.

Coming from an American standpoint, it's surprising that prosecutors wouldn't close the book on the case after one surefire guilty verdict; in the U.S., prosecutors tend toward a path of least resistance. The overzealousness and outsized passion of investigators attempting to pin it on Knox cannot be overstated; it was these passions, more than the evidence, that led to her multiple convictions. Why Knox and Sollecito weren't released, or at least the accusations against them heavily re-examined in light of Guede's guilt, is a shocking mystery, not to mention a miscarriage of justice.There's a prosecutorial greed here that doesn't make sense.

The media's incendiary reaction

"This has gotten out of hand." Such was Knox's reaction, delivered in writing, to having been tried in absentia and convicted of murder a second time in 2014. Talk about an understatement—it was out of hand well long before.

One of the reasons actual answers—real resolution—have been so hard to come by during these trials, and this whole ordeal, has to do with perception. Think about these words from Rod Blackhurst, one of the directors of Netflix's upcoming documentary, Amanda Knox: "The way they were talked about was like they'd become characters in some Hitchcockian nightmare about a story like this. None of them—Mignini, Knox, Sollecito—felt the portraits that were being painted were representative of them as individuals."

Channeling the grand did they or didn't they storytelling tradition recently wielded so effectively by the Serial podcast, HBO's The Jinx, and Netflix's own Making a Murderer docuseries, Blackhurst and co-director Brian McGinn crafted a narrative that's less about the crime and more about the characters—the innocent, and the accused. What does it mean to be the focus of an international witch hunt? What happens to a person when they're cast under suspicion, and how the world sees them starts to bend under a barrage of innuendo?

One of the greatest injustices against Amanda Knox is still being committed against her—the slander of her name. She'll never not be associated with the murder of Meredith Kercher, despite her innocence, and that's not on her—that's on the circus that surrounded her. Some people still believe she did it, and thanks to the provocative nature of her trials, and the sordid qualities of the accusations against her, some people surely always will.