Olympic Athletes Who Hit Rock Bottom

Once the cauldron is extinguished, the medals are distributed, and the cheers fade, Olympians often face the toughest challenge of all: real life outside of their sport. Adapting to a place in normal society is no easy task when your whole life has revolved around training for a specific sport. Some Olympians were able to recover and come back as inspiring examples, when many others weren't as lucky. Whether it was due to bad luck or poor decisions, these athletes went from the Olympic pedestal to rock bottom.

Joe Greene

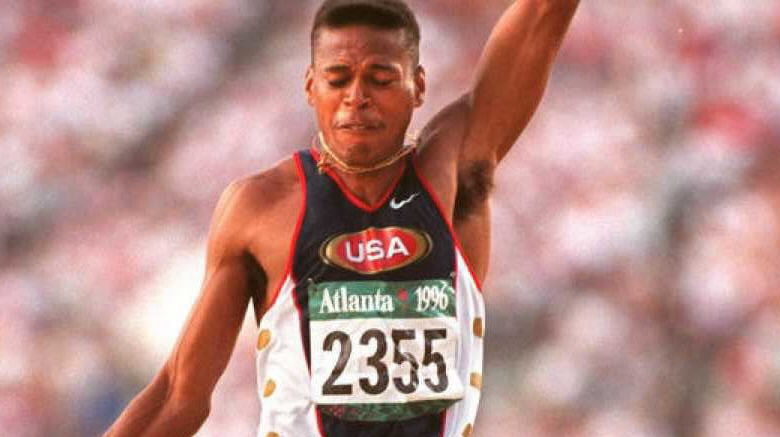

Jumpin' Joe Greene took home the bronze medal in the long jump at both the 1992 Barcelona and 1996 Atlanta Olympic games. Over the next seven years, Greene's life spiraled out of control. He suffered from a connective tissue disorder—forcing his retirement from the track—and he went through a messy divorce afterwards. By 2003, he was desperate when he wandered into Rick Harrison's Las Vegas pawn shop—the one featured on the television show Pawn Stars.

"I think it's all he had left," said Harrison. Greene ended up pawning his bronze medals, which Harrison vowed to never sell in case Joe ever wants to buy them back. As of 2012, Greene had not reclaimed his medals, but he has reclaimed his life. He's gotten married again, and works as a recruiter in the healthcare industry.

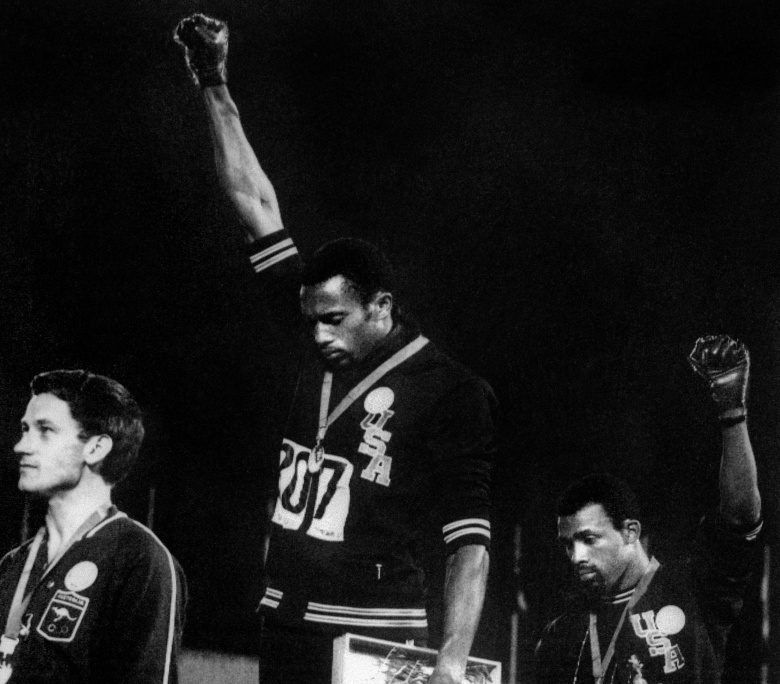

Peter Norman

The silver medal finisher in the 200m race at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, Peter Norman was the third guy on the podium when gold and bronze medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their fists in a Black Power salute. While Carlos and Smith were hailed as heroes upon returning to the United States, Norman was treated as a pariah in Australia—where apartheid laws were common during this time. His support for Carlos and Smith was viewed by many Australians as shameful, and Norman was not allowed to participate in the 1972 Munich Olympics, despite qualifying several times. His 1968 200m record of 20 seconds flat would have won the event even at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. Even though he wouldn't live long enough to see it (he died of a heart attack in 2006), Australia's parliament issued a formal apology to Norman in 2012.

Anthony Ervin

After earning gold in the 50m freestyle swimming event at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, Anthony Ervin dropped out of the sport completely. He fell into a rock-and-roll lifestyle—joining a band, getting addicted to hardcore drugs, and squandering his money. Ervin battled with alcoholism, drug abuse, and depression during this period—attempting suicide more than once.

In 2011, Ervin rebounded. He sobered up, received his bachelor's degree, and got back in the pool. He qualified for the 2012 London Olympics and finished fifth in the 50m freestyle. Finally, 16 years after he first won gold in Sydney, Ervin took home the gold medal yet again in the 50m freestyle at the Rio Olympics, becoming the oldest individual swimming gold medalist in Olympic history.

Jeret Peterson

After a troubled childhood that included the death of his sister and being a victim of sexual abuse, three-time Olympian Jeret Peterson found an outlet in the world of freestyle skiing. His adult life was marked by turbulence and tragedy. After his roommate committed suicide in front of him in 2005, Peterson turned to alcohol and eventually was kicked out of the 2006 Vancouver Olympics following a drunken incident.

After taking a couple of years away from the sport, Peterson returned to the Olympics in 2010 and won the silver medal in the aerials event with his signature "Hurricane" jump. Bad memories and the pressures of real life closed in again after the games, and Peterson was arrested on DUI charges in 2011. This time, Peterson wasn't able to recover, and sadly, he ended up committing suicide only three days after his arrest.

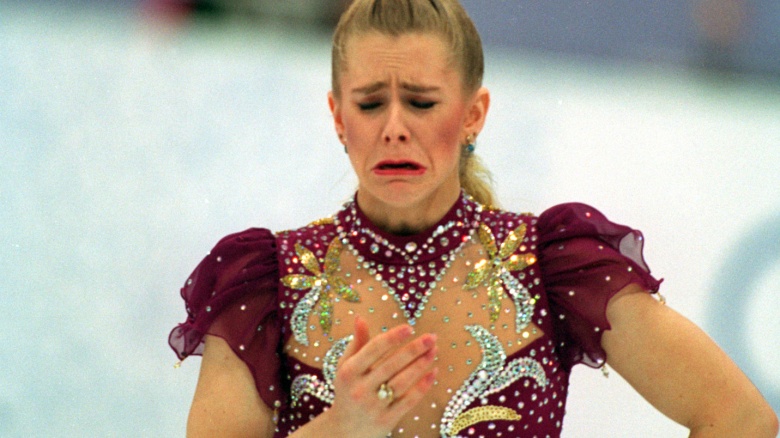

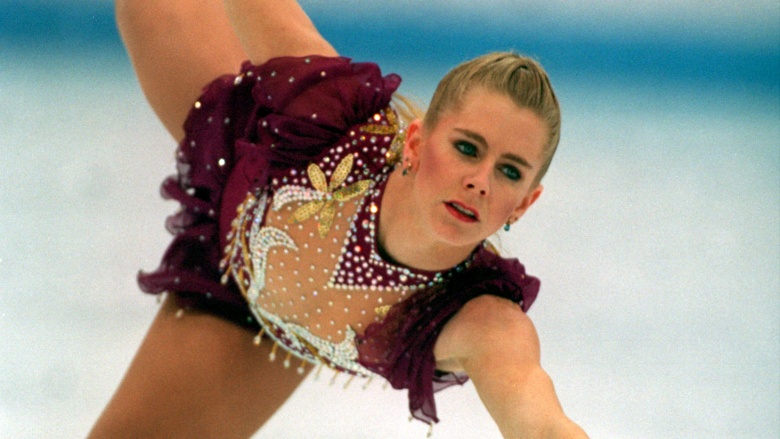

Tonya Harding

In 1992, Tonya Harding was near the top of the world of women's figure skating. She finished a respectable 4th at the 1992 Olympics. The next winter Olympics would be held in 1994, and Harding wanted to be ready for it. Unfortunately, her preparations included a sinister plot to take out her biggest rival, Nancy Kerrigan. Harding's ex-husband hired a man to surprise attack Kerrigan after a training session, injuring her knee with a police baton. Kerrigan was taken out of competition long enough for Harding to win first place at the 1994 U.S. Championships.

Kerrigan recovered in time to win the silver medal at the 1994 Olympics, while Harding—hounded by paparazzi and investigators—finished a dismal 8th. After her complicity in the attack was discovered, Harding was stripped of her 1994 U.S. Championship title and banned from competitive figure skating for life.

Oscar Pistorius

Double amputee Oscar Pistorius made history when he became the first disabled runner to win a medal in a non-disabled race at the 2011 World Championships. Subsequently, Pistorius was selected to the South African 4x400m relay team for the 2012 Olympics in London. Although the team didn't earn a medal, Pistorius made history yet again by becoming the first amputee runner to compete at an Olympic games.

A year after his Olympic debut, Pistorius shot his girlfriend through a closed bathroom door. Pistorius claimed he had mistaken her for an intruder and was initially convicted of manslaughter. A prosecutorial appeal reversed that decision in 2016, upgrading his conviction to murder and sentencing him to six years in prison.

Marion Jones

In 2000, Marion Jones' stardom was ascending—she'd won three gold medals and two bronze at the Sydney Olympics and was making millions in endorsement deals. It all came crashing down several years later, when Jones was caught up in a doping and money-laundering scandal. She also admitted to taking performance-enhancing drugs. Jones was subsequently stripped of her medals by the International Olympic Committee before being sentenced to six months in prison for check fraud.

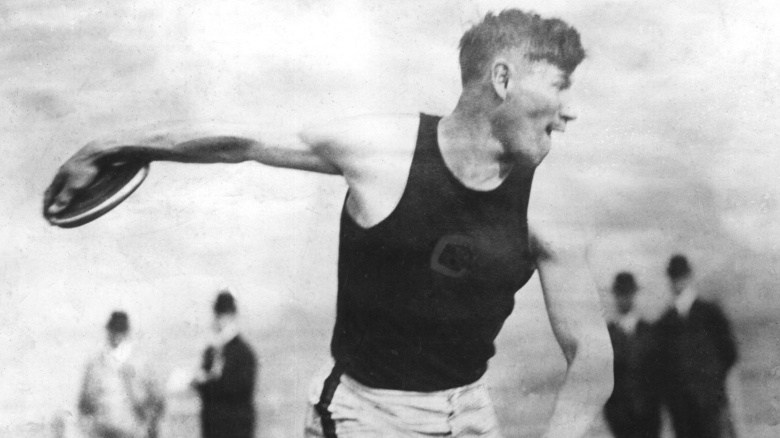

Jim Thorpe

Considered by many to be the greatest athlete of the 20th century, Jim Thorpe was dealt a very raw deal by the International Olympic Committee. At the Stockholm Olympics of 1912, Thorpe won the gold medal for the United States in the decathlon and the modern pentathlon—two brand new events for the 1912 games. About six months after the games ended, rumors began to circulate about Thorpe's professional sports history. It emerged that Thorpe—like many of his college peers of the era—had played semi-professional baseball during the summer of 1909. Even though the complaint had been brought well beyond the 30-day limit in the IOC's rulebook, the IOC stripped Thorpe of his gold medals.

Many historians now see this decision as a sign of racism directed towards Thorpe, as his era was marked by large racial inequalities aimed towards Native Americans. Thorpe would go on to have a successful college and professional career in basketball, baseball, and football; but his life after retiring from sports was plagued by poverty, alcoholism, and poor health. He died in 1965, near penniless—his wife actually sold his remains to a tourist-seeking town in Pennsylvania in order to pay for his burial. While he never lived to see it, Jim Thorpe was redeemed in 1982, when the campaigns of his family and members of Congress finally paid off. The IOC reinstated Thorpe's amateur status, and presented two of his children with commemorative gold medals.