What Tim Montgomery's Life In Prison Was Really Like

This article contains references to substance abuse and suicide.

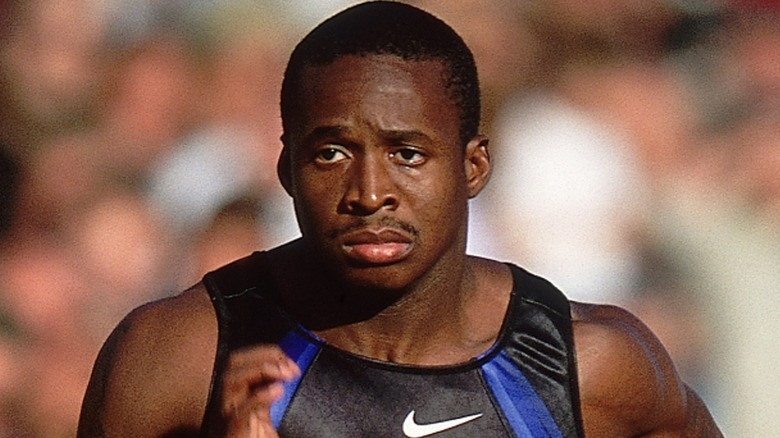

Tim Montgomery first rose to prominence at the 1996 Olympic Games when he won a silver medal with the 4×100-meter relay team in Atlanta, Georgia. Montgomery eventually set a world record for the 100-meter dash in September 2002 at the 18th IAAF Grand Prix Final. His popularity grew, not only because of his outstanding 9.78-second achievement, but also because he went public with his relationship with fellow athlete Marion Jones. Jones had won the women's 100-meter final at the same event and secured a reported $100,000 cash prize.

The couple's rise to the top was spectacular, but their downfall was just as loud. Both Montgomery and Jones got caught up in the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO) scandal, in which several athletes were accused and found guilty of doping. In mid-December 2005, Montgomery was given a two-year ban by the Court of Arbitration. Subsequently, his prestigious titles were revoked. It didn't take long before he informed the public of his early retirement. While Montgomery's offense was a big blow to the athletic world, it surprisingly wasn't the reason he served time. Keep scrolling for a detailed account of the circumstances that got him locked up and how his life unfolded afterward.

Why was Tim Montgomery in prison?

In April 2006, Tim Montgomery was taken into custody and charged alongside 12 other suspects for bank fraud and money laundering. Per The New York Times, Montgomery was indicted for depositing three checks which amounted to a $775,000 total. He'd also received $20,000 from his former coach Steven Riddick, who was a co-accused.

Montgomery pleaded guilty in a Manhattan court in April 2007. He expressed remorse in a statement to the press, saying (via The New York Times), "I sincerely regret the role I played in this unfortunate episode. I have disappointed many people, and for that I am truly sorry. I look forward to moving past this event and being a positive influence in my community in the future." Montgomery was given a 46-month sentence by New York Judge Kenneth Karas in May 2008.

During the course of his legal woes, Montgomery had taken to dealing heroin in order to raise funds, as he shared in a 2016 interview with "Trans World Sport." The gravity of his offense didn't dawn on him until he got caught. "When they put the cuffs on me for selling heroin and told me how bad heroin was — how much time I was facing — I really, really wanted to die then," he told the outlet. In October 2008, 33-year-old Montgomery was sentenced to an additional five years for possession and distribution of the drug.

He moved from one rowdy prison to another

In an interview with The Times, Tim Montgomery revealed that the early years of his sentence were spent in unruly prisons. There was never a sense of calm, and fights between prisoners were rampant. "Guys had shanks — homemade knives — and it seemed like someone was stabbed every day," Montgomery recalled. Not that Montgomery's hands were always clean. In one instance, he was part of a group of convicts that exchanged blows in a mega fight and was mistakenly singled out as the mastermind. At a New York prison, he physically assaulted a pedophile cellmate to earn the admiration of other prisoners.

Besides perpetrating and witnessing violence, prison forced Montgomery to rethink his position as a drug peddler. At Portsmouth City Jail in Virginia, he was locked up in a bullpen with offenders who abused drugs and were suffering from withdrawal symptoms. Watching their struggle prompted Montgomery to self-reflect. "Some of them people was never on the level that I was on," Montgomery recollected on "In N Out Podcast." "My circumstances was a lot better than ... the circumstances they probably had. And for me to put myself on top of them and make their circumstances even worse, you have to question on who you are."

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

He contemplated suicide out of despair

Tim Montgomery hadn't experienced an anxiety attack until he was incarcerated, as he shared in his chat with "Trans World Sport." Prison took a toll on his mental health, and he had a fit of panic that resulted in suicide ideation. "I really was trying to find a way to end my life," Montgomery told the outlet.

He went into more graphic details of the unfortunate events that transpired in his cell in a conversation with Prison Fellowship. "I got up on top of the bunk and looked at the commode, and said, 'I'm gonna' fall and try to break my neck or break my head on the commode.' Then I was like, 'Oh, what if I don't succeed? That's going to hurt,'" Montgomery shared, and continued, "So then I cut the sheets and tried to hang myself, and every time I got to the point of choking I stopped."

At that moment, Montgomery had a spiritual epiphany that suddenly changed the trajectory of his life. He discovered God and familiarized himself with the Bible. Afterward, he linked up with a former associate from the streets who'd become a pastor. Montgomery worked with him to help strengthen his conviction.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

He settled at the nonviolent Federal Prison Camp (FPC) Montgomery

After moving around different prisons, Tim Montgomery finally served time at Federal Prison Camp (FPC) Montgomery, a minimum-security correctional facility at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. Maxwell Air Force Base is a training ground for aspiring Air Force professionals, courtesy of Air University. It also accommodates numerous civilians who work there.

Beyond its school-setting, it has a homey feel, which features well-manicured residences and amenities like a playground, a horse stable and a grocery store. FPC Montgomery is located at the extreme end of the premises. It houses nonviolent felons who have committed white-collar crimes such as wire fraud, embezzlement, immigration fraud, and corruption, all of whom have sentences of 10 years or less.

Tim Montgomery was inmate No. 56836-083, and at the time he was locked up, there were a total of at least 900 inmates. Though the facility was generally low-risk, it didn't change the fact that he wasn't as free as those who roamed in and out of Maxwell Air Force Base. "It may not look too bad, but it is prison," Chalon Moore, a representative of the prison, told ESPN in 2009. "You can't leave."

Tim Montgomery had no star power when he was incarcerated

At his peak in the athletic world, Tim Montgomery's fame came with major perks. Money wasn't a problem since he charged up to $60,000 to compete at events and fetched $575,000 annually from a contract with giant shoe retailer Nike. He also had the luxury of living in the same neighborhood with six-time NBA champion Michael Jordan.

In prison, however, Montgomery came to learn that the star power he had as an athlete wasn't as strong as it seemed. From the get-go, he was treated like other inmates and had to trade his flashy clothes for a prison uniform. "I went in thinking that I had to have all these designer this, designer that, and when you get to prison, you got a green visitation suit, some sweats, and some ... green work clothes with a brown shirt. And that's the way you live," Montgomery revealed in an interview with Manager Marty.

Despite having major accolades, including a 4×100-meter Olympic gold medal secured at the Sydney Games in 2000, none of Montgomery's fellow inmates recognized him. "In here, people say, 'Oh, we haven't really heard of you.'" Montgomery shared in an interview with ESPN. "Then it's, 'You had the world record? OK, now we know.' That means something."

He made a living as a landscaper

According to Federal Prison Camp (FPC) Montgomery guidelines, inmates have an array of revenue-generating apprenticeship activities to choose from, including plumbing, housekeeping, electrical work, and landscaping. During his time at the facility, Tim Montgomery's income was nothing like the six-figure checks he had been accustomed to during his glory days.

He worked as a landscaper earning $0.12 per hour. Per his chat with ESPN, he took care of Maxwell Air Force Base lawns during morning hours and in the afternoons. His day typically began at 5 a.m., as The Times noted. At 5:30 a.m., he would join other inmates for breakfast, and an hour later, he'd begin work. The routine remained consistent throughout his sentence.

In his chat with The Times, Montgomery couldn't help but express his dissatisfaction with what his life had become. "I had the best job in the world — now I'm in prison clearing leaves," he told the publication. Long after Montgomery had left prison, inmates at FPC Montgomery earned better wages. Per the facility's Admission & Orientation Handbook, the pay as of April 2022 ranged from $0.23 to $1.15 per hour.

Tim Montgomery coached and trained with other inmates

Tim Montgomery didn't abandon his athletic background in prison. As he served time, he laid the foundation for his future career as a coach by training fellow inmates in the evenings. He also helped them transform their bodies through well-drafted meal plans, per USA Today. Montgomery was so good at the job that some prison wardens got into his program.

While he was helping other people smash their body goals, Montgomery had some dreams of his own. First, he stayed on his best behavior so he could have a chance to leave earlier than his January 2016 release date. Second, his biggest goal was to return to the track and reclaim his former glory. "I'm training, running," Montgomery shared in his conversation with ESPN. He often went up against other inmates, many of whom gave him a run for his money — no pun intended. "You can't believe the raw talent in jail that is behind bars. And they're ready to challenge you," he told the publication.

He became a bookworm and began writing a memoir

Tim Montgomery had a superficial relationship with books before he was imprisoned. He'd purchase them for only one purpose — to fit in as he flew first class. His interest in reading changed when he began serving time. He read several books at FPC Montgomery, including each edition of Stephenie Meyer's fantasy romance series, "Twilight." Montgomery not only developed a reading habit, but he also began drafting the manuscript of his life story.

He eventually partnered with former British 60-meter hurdle star Liam Collins to bring his biography "Project World Record" to life. Both Collins and Montgomery have something in common — they were once glorified athletes whose lives took a disgraceful turn. Per The Financial Times, Collins reportedly got in trouble with the law for running an unauthorized real estate investment firm that duped investors of funds amounting to $5 million with the promise of a 10% annual return. Just like Montgomery, he turned over a new leaf and even helped expose the world of athlete doping in a controversial Al Jazeera documentary. At the time of writing, his collaboration with Montgomery is yet to be published.

He tied the knot with his on-and-off girlfriend, Jamalee Montgomery

Tim and Jamalee Montgomery first crossed paths in 1999. The relationship between the then-lovebirds was flaky since they would often break up and make up. They had a daughter, Tymiah, who was born prior to his relationship with Marion Jones. At the height of Tim's fame, he took his family for granted. "He had different goals, and family wasn't it at the time," Jamalee said during the couple's interview with USA Today.

The duo eventually rekindled their relationship and tied the knot in prison in October 2009. Tim's family became his biggest support system, as he shared in an interview with The Virginian Pilot. He and Jamalee talked to each other frequently, and every month, she would drive for seven hours from Gainesville, Florida, to see him.

Their daughter, Tymiah, took after her dad and became an athlete in her own right. During visiting hours, Tim would give her advice on how to be better on the track. Although he tried his best to be a good father, Tim understood that his circumstances portrayed a different message. "When your kids come to see you, how can you tell them to be good when you are here in prison?" He asked in his chat with The Times.

He lost contact with Marion Jones

Tim Montgomery's ex-partner Marion Jones was also implicated in the check fraud that got him incarcerated. Montgomery admitted that he'd lured her into the scheme, and as a result, they weren't on good terms. In January 2008, Jones was handed a six-month sentence. She was also subjected to two years of supervised release and 800 hours of community service, per ABC.

By the time Montgomery was sentenced in May 2008, he and Jones had already lost touch. She'd moved on with Obadele Thompson. Montgomery tried to initiate contact later, but there was no reciprocation on Jones' side. "I wrote [Jones] a letter and said I was sorry for what I had done. She never wrote back," Montgomery revealed in his interview with ESPN.

The ex-couple has a son, Monty, who was born in June 2003. He, too, wasn't in touch with Montgomery when he was behind bars. "I have no connection with my son. It bothers me a lot. That's one of the reasons why I sat down and wrote [a book]," a distraught Montgomery told ESPN. "I came to jail and she did, too, but she makes it seem like mine is worse. No mother should keep a child away from his father unless he's hurting the child." Jones' move was quite deliberate, since Monty and her other child, Amir, didn't visit her in prison, either.

When was Tim Montgomery released from prison?

Tim Montgomery's plan to secure an early release date paid off. He left FPC Montgomery in May 2012 and was sent to a halfway house in Gainesville, Florida, where he worked in construction. After three months, he was placed under house arrest. Adjusting to life after prison wasn't a walk in the park, especially since Tim had to get to know his family all over again. "At first, it was hard," Tim's then-wife Jamalee Montgomery told The Virginian Pilot. "Because I was used to running the household and was in charge of everything and then when he came home, he wasn't used to being a dad or a husband."

The couple launched a coaching business dubbed NUMA Speed in 2013. NUMA is an acronym for "Never Underestimate My Ability." Once again, Tim's financial muscle began to strengthen since he had numerous clients. In 2019, Jamalee and Tim divorced, as she revealed in a conversation with Voyage Tampa. As of August 2024, NUMA Speed Elite is still up and running. Tim has a new crop of friends, and they were all made in prison. "We built a bond that you cannot build on the streets," the ex-athlete told the Daily Mail.