What Life Was Like For Marion Jones Before The Olympics

Marion Jones was barely into her teen years when the promising young athlete began earning a reputation as America's next great track star. She proved those predictions to be right on the money when she competed in the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, making history as the first female athlete to win five medals in track and field in the same year.

In 2007, it all came crashing down when Jones confessed to taking steroids; the International Olympic Committee subsequently stripped her of all her medals. Meanwhile, she was in dire straits financially when a bank foreclosed on her home the same year. The athlete was subsequently hit with charges of lying to federal agents about her steroid use, and also admitted to lying about her knowledge of a check-forging scheme involving her former sports agent. Jones was sentenced to serve six months in prison, and was released in September 2008.

Yet that wasn't the end of her career in sports. In 2010, Jones was signed by WNBA's Tulsa Shock. While her new basketball gig was seen by some as Jones seeking redemption, she took a contrary view. "Redemption isn't a part of my vocabulary," Jones said during a news conference, as reported by The New York Times. The following year, she was cut from the team, and transitioned into working as a sales executive. With all that in mind, read on for a look at what life was like for Jones before those fateful Olympic Games.

Marion Jones turned to sports to cope with grief

Marion Jones's mother and father divorced when she was a young child. She was still a kid when her mom — who had immigrated to the U.S. from Belize — married Ira Toler. While the future track star's mom worked as a secretary in a law firm, Toler was a stay-at home dad, taking care of Jones and her half-brother, Albert Kelly.

During those formative years, the youngster grew close to Toler, who — because her mother was also named Marion — nicknamed her "Little Marion." "Ira was always there for my sister," Kelly recalled to Sports Illustrated. "He talked to her, answered her questions, helped her with homework, took her to tee-ball games. Then he was gone."

Toler tragically died of a stroke in 1987 when Jones was 11 years old. She was understandably devastated by the loss. The following year, she began to develop an interest in track and field after watching Florence Griffith Joyner's amazing performance at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. Jones coped with her grief by throwing herself wholeheartedly into her new pursuit. That dedication paid off; by the time she was in high school, she was a top competitor, and her coach began to believe she could have a future as an Olympian.

She showed early promise in track and field

Marion Jones began competing in national track and field competitions when she was just 12 years old. While proving to be something of a prodigy as an athlete, she was a challenging daughter. "She was the type of child who would say, 'If I don't get this or that, I'm going to jump off this ledge,'" her mother, Marion Toler, told Sports Illustrated. "If I said, 'Go ahead, jump,' she would have. I knew that she would defy me, test me, and there were many rebellions."

However, Toler was also intuitive enough to recognize that the same rebellious nature that gave her headaches was also fueling the fire in her daughter that made her such a fierce competitor in her athletic pursuits. As a result, she tried to figure out how to teach Jones to harness those feelings in service of her athleticism. "But I decided that she was special, that I had to find a way to nurture these qualities," Toler explained. "not beat them out of her."

That strategy seemed to work. By the time Jones made it to high school, she was performing at a level far beyond the rest of her peers. She won numerous national competitions, running the fastest in the 100, 200, and 400-meter races while still a sophomore. When she was a junior, she posted a time of 22.58 running the 200 meters, setting a U.S. high school national record.

She skipped out on the Barcelona Olympics

While it was the 2000 Olympics in Sydney where Marion Jones made her mark — despite the controversy that engulfed the entire situation years later — she was initially seen as a serious contender for the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, nearly a decade earlier. As The New York Times reported on her at the time, the 16-year-old was seen as "possibly the greatest high school runner in history," and a likely champion to bring home some gold medals to America. So why did she decide to skip out on the international competition?

The answer was surprisingly simple, yet also tough for some people to swallow. According to Jones, her mother, and her high school track coach, she wanted to place the focus on her studies and finish high school before being drawn into a world of six-figure endorsement deals and high-stakes pressure. The risk, of course, was that the opportunity to compete on behalf of America might not come around again in four years. Jones, however, was willing to take it.

Meanwhile, there a rumor also began swirling that she might evade Team USA altogether and instead compete for Belize, the country of her mother's birth. When Olympic Coach Sue Humphrey heard about that possibility, she told the Times that there would always be a spot awaiting Jones on the American team. "We want Marion on our team," Humphrey said. "The old-timers can't go on forever. She's our future."

Jones also garnered attention as a basketball player

At the same time that Marion Jones was burning up the track, she was also demonstrating some serious skill on the basketball court. As a high school basketball star, she led her high school, Thousand Oaks High, to the regional championship ... twice! In 1993, her talent was recognized when she won California's Division I Player of the Year award. So formidable were her skills that Jones then went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on a basketball scholarship.

This was a smart move for the college, given that she went on to help the women's basketball team take the national title in 1994. Jones' phenom status in both track and basketball did not go unnoticed; In fact, she was the subject of a brief item in a 1995 edition of The New York Times detailing her dual athletic pursuits. "She is happy that she is playing basketball in the winter and running track in the spring and summer," the article noted. "And if you think she is ruining a world-class career as a sprinter by spending the winter as a starting point guard, that's your problem."

"Her preseason conditioning takes place on her high school's basketball team," her track coach, Elliott Mason, told The New York Times while she was attending high school in 1992. "I have to hold my breath during basketball season that she doesn't get injured."

Injuries prevented her from competing in the 1996 Olympics

After Marion Jones' decision not to compete in the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, she cast her eye on the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. In fact, in the four years between those two events, Jones dedicated herself to relentless training to be ready for what she knew would be the toughest and most nerve-racking competition she'd ever experienced. As it turned out, though, she did not compete in Atlanta, and this time, the decision was not hers.

Jones wound up suffering a foot injury, breaking a bone in her left foot and then breaking it again when she didn't give herself enough time to fully recover. As a result, she was unable to try out for a spot on the U.S. women's track team. That broken bone proved to be a huge setback for her athletic career, as she was forced to sit out the entirety of the 1996 track and field season when she broke the bone for a second time.

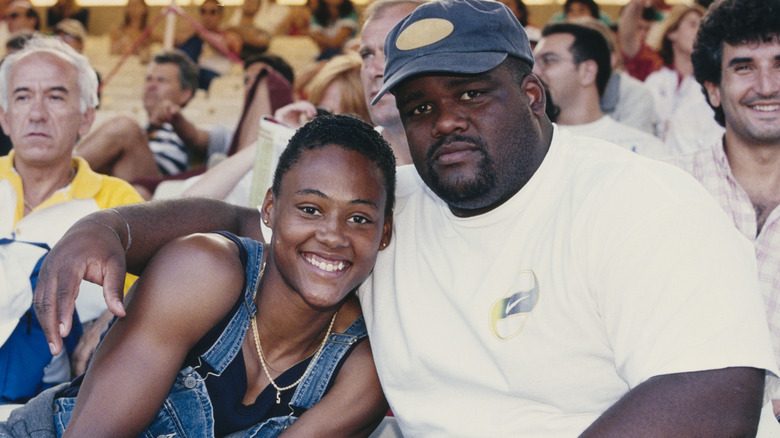

Her dreams of Olympic gold postponed, Jones was recuperating from her injuries when she met C.J. Hunter, a shot-putter and coach at the University of North Carolina. This relationship would go on to play a major role in her life over the next few years.

Dating her college track coach forced him to resign

When Marion Jones began dating C.J. Hunter, the relationship raised eyebrows. Not only was Hunter seven years older than she was, but he was also working under Jones's coach, Dennis Craddock. Because university regulations strictly prohibited coaches from dating the students, rather than breaking it off, Hunter instead offered his resignation. "Easy call," Hunter assured to Sports Illustrated.

The relationship progressed quickly, and it wasn't long before the two were engaged. Not everyone was happy about the romance, however. "There are a lot of people who care about Marion who feel that C.J. is not good for her," said Sylvia Hatchell, Jones's college basketball coach. As the publication pointed out, Hunter was a divorced father of two children, and had previously filed for bankruptcy, described as being "large and menacing and very economical with words."

Hunter also had his supporters, though; former UNC coach Jeff Madden, who introduced the two, insisted that Hunter was misunderstood. "People are intimidated by him because he's blunt," he said. Hunter, however, had his own view about the negative attention their relationship was attracting. "People who criticize us don't give a damn about Marion," he said and also shared a theory about why Jones's basketball coach said what she had. "Hatchell was thinking about her own team," he added. The two married in 1998, but the marriage didn't last long. They divorced in 2002. Hunter died in 2021 at age 51.

Jones aimed to be the fastest woman in the world

With her sights set on the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Marion Jones set an ambitious and audacious goal for herself. By the time she set foot on Australian soil, she intended to be the fastest female runner in the world.

Speaking with The New York Times in 1997, Jones believed that if she continued training at the level she was working, she would eventually be able to break the impressive world records set by American runner Florence Griffith Joyner for the 100 and 200-meter races. Jones did, however, admit that breaking those records could be some time away. ”It will definitely stand for a couple more years,” Jones told the publication about Griffith-Joyner's 100-meter record. ”I hope I'm the person who can break it. It would have to be a perfect day, a perfect race, but I feel I can be that person. Hopefully in a couple of years I will be able to say I'm the fastest woman who ever lived.”

Given that she deliberately skipped her first opportunity at Olympic gold and was denied a second by an injury, Jones was asked how long she was going to continue competing in track and field. ”I'm not going to say forever,” she replied. ”But definitely several more years. I want to achieve the things I've dreamed all my life. I want to be world champion, an Olympic gold medalist and a world record-holder.”

She was heralded as the next great women's track star

Setting a goal of becoming the world's fastest woman might seem a far-fetched pursuit. In the case of Marion Jones, however, the question seemed to be not if, but when she would achieve her goal.

She came several steps closer to that aim when she began working with coach Trevor Graham. A former athlete, Graham had devoted himself to reading manuals on running technique and working with top athletes and wanted to put all the information he'd gleaned into practice. "Here I'm getting all this knowledge," Graham told Sports Illustrated. "And I just needed a great sprinter so I could teach it." When he first watched Jones training, he took the initiative to offer her some advice, a minor adjustment to her running technique. The results were immediate, with Jones instantly running faster and better than she ever had before. "It was, like, automatic results," Jones said. "That had never happened to me."

Those improvements were not only noticeable, but they contributed to her winning key competitions in the lead-up to the 2000 Olympics. It wasn't long before she began to be discussed as the next big female track star. Even Olympic athlete Jackie Joyner-Kersee concurred. "I don't know what she can't do," Joyner-Kersee told Sports Illustrated of Jones. "She's gifted and she's mentally tough. She can own everything from the 400 on down, plus the long jump."

Jones dazzled at the 1998 Goodwill Games

Thanks to the adjustments to her technique she gleaned from working with Trevor Graham, Marion Jones was hitting her stride when she headed to New York to compete in the 1998 Goodwill Games. As The New York Times reported, she easily dominated the women's sprinting events, with her time in the 200 meters being the fastest of any runner that year.

"Many think that she has a solid chance to break Florence Griffith Joyner's world record, which is 21.34. Jones won the 100 on Sunday night and has won 23 consecutive events this season without a defeat," noted New York Times reporter Jere Longman.

Meanwhile, the Associated Press added some details that made her performance at the games all the more impressive. First, Jones had to restart the race after a false start, which is something that would easily rattle any athlete. Meanwhile, she was also running straight into a 2-mile-per-hour headwind. Despite those obstacles, she nonetheless managed a time of 10.90 seconds in the 100 meter. While that proved to be her second-slowest time of the year in that particular event, it also marked the eighth consecutive running of that race in which she came in under 11 seconds — something that no other sprinter had ever managed to do more than six times in a row.

Mid-race back spasms set her back in 1999

In 1999, Marion Jones was the woman to beat when she took to the track for the Track and Field World Championships in Seville, Spain. By that point, Jones had been dominating the sport for some time, and expectations were high that this could be her finest performance yet. In an unexpected turn of events, The New York Times reported that Jones's usual "aura of invincibility" was pierced when, mere seconds into the race, she doubled over in pain, grasping at her back and then crumpling to the ground. Doctors rushed in to attend to what appeared to be cramps and spasms in her back.

Fans watching were stunned, as were her fellow athletes. "It's tragic," Australian sprinter Nova Pedris-Kneebone told the Associated Press. "In my eyes, she's the Wonder Woman of track and field. She's gained so much respect." After receiving medical attention, Jones was not only forced to pull out of the World Championships, but also wound up sitting out the remainder of the season.

After the major setback of pulling out of the 1999 track and field season due to her back spasms, Jones was nonetheless looking ahead to 2000. Her agent, Charlie Wells, told the Tampa Bay Times she was confident that not only would she compete in Sydney, but was gunning to win a record-breaking five medals.