What Happened To Former Olympic Athlete Marion Jones?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Sports history often focuses on memorable people doing extraordinary things, and every generation has many well-known athletes. The 2010s and 2020s focused a lot of attention on Simone Biles' numerous accomplishments, and in the early aughts, Marion Jones was the name on everyone's lips. Jones was a preeminent track star, excelling through high school and college and winning numerous track and field titles and championships.

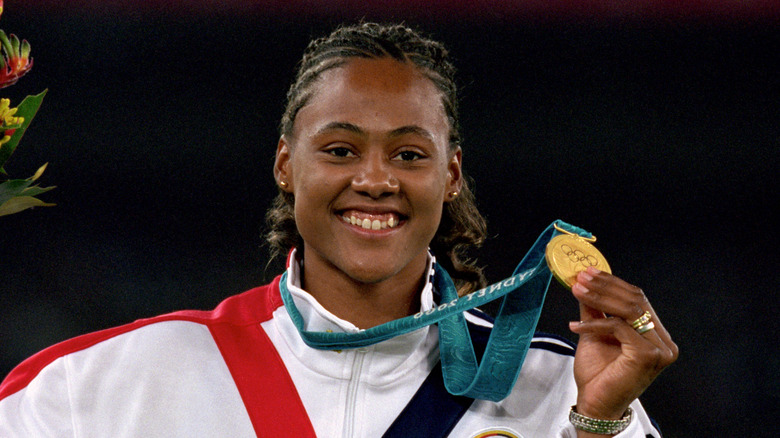

Jones made it to the 2000 Olympics and took home three gold medals and two bronze, so she was at the top of her game at the onset of her professional career. Before long, Jones became embroiled in controversy as allegations of steroid use tarnished her public image. The scandal ultimately took Jones down, ensuring her career as a track and field star ended just as it was beginning. Still, being a disgraced athlete didn't keep Jones down forever.

With some work, Jones found her way into new areas of sports and fitness, and she continued to live her life much as she did before the scandal. Of course, Jones has faded from the limelight, which leaves many wondering what happened to her. For years, Jones' name was in the headlines for good and bad reasons, but you don't hear much about her anymore. This is what happened to Marion Jones and what she's been up to since her career veered off-course following a doping scandal.

She married her track coach and trained hard

Marion Jones found her way to athletics through her half-brother, Albert Kelly. She picked up basketball and track as a way of connecting with him, and she excelled. While Jones didn't make the 1992 U.S. Olympic team, she came close and continued training hard throughout the 1990s to earn her spot. In college, Jones played basketball, helping lead her team to the NCAA Women's Championship in 1994, but she also continued working hard on the track.

Jones met her future husband — shot putter C.J. Hunter — while attending the University of North Carolina. Hunter worked as a track coach for the school, and the couple married in October 1998. From that point forward, Jones devoted most of her time to training and competing in international track and field events.

While training and competing, Jones set her sights on representing the U.S. at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia. She worked with her husband to achieve her goal and ultimately made it onto the U.S. Olympics track and field team. Once on the team, Jones spent all of her time preparing for the international competition, and she even declared she'd win five gold medals in all of her events — a bold move, to be sure, but one that wasn't entirely unfounded.

She competed at the 2000 Olympics

While there are many international sporting competitions, the Olympics are inarguably the most difficult one to get to due to the overwhelming competition. Still, Jones worked hard and made it onto the U.S. track and field team for the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. Jones trained for and competed in four events: the 100-meter, 200-meter, 4x400-meter relay, 4x100-meter relay, and the long jump. Each event came with its own challenges, and Jones was ready to win the gold.

Having declared she'd win all five events to take home the gold, the pressure was on. Of course, the pressure was already on, seeing as it was the Olympics, but Jones was laser-focused on achieving her goal. She ultimately won five medals, becoming the first woman to do so at a single Olympics. Jones won gold in the 100, 200, and 4x400-meter relay, and she took home the bronze in the other two events.

Jones' husband, C.J. Hunter, pulled out of the shot put competition due to an injury but stayed on as her coach. Shortly after Jones won her first event, news broke that Hunter failed his pre-Olympic drug tests. He tested positive for the anabolic steroid nandrolone, earning a suspension and the loss of his coaching credentials. The scandal cast a negative light on Jones' drug-free image, and it adversely affected their marriage, which ended in divorce in 2002.

She became a mom in 2003

Marion Jones' first marriage ended in divorce without any children, and she would marry again. Before that could happen, Jones began seeing the then-world-record holder of the 100-meter event, Tim Montgomery. The couple dated for some time and eventually had a son, Timothy "Monty" Montgomery Jr., who was born prematurely. Montgomery missed the birth of his son due to a competition in Glasgow, Scotland. He told the Los Angeles Times, "We knew we'd have a fast baby, but I didn't expect him to be this fast!"

Shortly after the birth, Jones issued a press release, saying, "I am so happy. This is the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. He's a beautiful baby, and Tim and I could not be more excited." Jones and Montgomery never married, and Jones moved on to a new relationship with fellow Olympic sprinter Obadele Thompson, who took the bronze in the 100-meter at the 2000 Olympics. The couple married in a quiet ceremony in early 2007 in Wilson's Mills, North Carolina.

Later that year, Jones and Thompson welcomed their first child, a son named Amir. Two years later, the family expanded once more with the birth of Jones' daughter, Eva-Marie. The family ultimately settled in Austin, Texas, where Jones launched her Take a Break program, which coached young people in making the right choices when presented with an important, potentially life-changing decision.

She starred in an IMAX film about incredibly fast people

Marion Jones' significant achievements at the 2000 Olympics made her a media darling. It didn't take long for Jones to appear in all kinds of places, including the covers of Vogue, ESPN, and Time. Jones made appearances on "The Tonight Show with Jay Leno," "The Rosie O'Donnell Show," the "Late Show with David Letterman" and more. As her handlers paraded Jones around the country, she found new opportunities off the track and in the realm of unscripted television.

Jones appeared as a contestant on shows like "Pyramid" and "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire," but her biggest foray into the media was the 2003 IMAX film "Top Speed." The film documents Jones and other "uncommonly fast individuals" using incredible visuals, CGI, and special effects. Tim Allen hosts "Top Speed," which visually depicts how incredibly fast Jones and the other amazing athletes in the film are.

After "Top Speed," Jones' media appearances coincided with her ongoing legal issues, so she appeared on "The Oprah Winfrey Show," "Good Morning America," and other similar programs. She scored one role in a scripted series, appearing as a fictionalized version of herself in a single episode of "Arli$$" in 2001. Jones returned to speak with Oprah in 2013 on her show, "Oprah: Where Are They Now," which revisits Oprah's most memorable guests to find out what they've been doing since appearing on her show.

She fought off allegations of steroid use

Marion Jones fought off allegations of steroid use throughout her career. Allegations go back to her time in high school after she missed a drug test. The school suspended Jones from competing in track and field competitions for four years. Jones appealed the suspension, claiming she never received the letter notifying her of the drug test, and she didn't do it alone — Jones hired famed attorney Johnnie Cochran to defend her, and he succeeded in overturning the suspension.

That was only the beginning of Jones' association with the alleged use of performance-enhancing drugs, but it wouldn't be the last. Jones' college career also saw allegations she used PEDs due to the close association she had with others. Jones had a penchant for working with coaches who found themselves on the wrong side of a steroid scandal. Her first husband and coach, C.J. Hunter, tested positive for steroids multiple times, earning a disqualification from the 2000 Olympics.

Most notably, Jones' name came up during the BALCO scandal, a scandal associated with the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative. The federal government investigated BALCO in 2002, and the findings of that investigation implicated dozens of athletes in a systematic distribution of PEDs, including various types of hormones, stimulants, and steroids. Jones vehemently denied she used any banned substances, and she never failed a test, even going so far as to dare the Anti-Doping Agency to charge her in 2004.

She admitted to lying about her steroid use

Marion Jones maintained that she didn't use steroids at any point in her career for years. Unfortunately, the BALCO scandal and her ex-husband implicated her with a lot of evidence, and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency opened an investigation into the athlete. Victor Conte, the founder of BALCO, testified he personally helped inject Jones with steroids before and after the 2000 Olympics. Her ex-husband also admitted to helping Jones take steroids, but she never failed a test, so the federal government didn't bring charges.

Jones failed a preliminary drug test in 2006 after testing found Erythropoietin in her urine. A subsequent test didn't find any, so Jones cleared her name with the help of an attorney. Finally, on October 5, 2007, Jones held a press conference and admitted to lying to federal investigators during the BALCO investigation. She also admitted to taking steroids before and after the 2000 Olympic Games.

Jones' tearful admission brought a lot of negative attention her way, and it compounded her legal issues. Lying to federal investigators is a crime, and Jones faced a maximum possible sentence of five years in prison if convicted. During the BALCO investigation, Jones denied she used the steroid Tetrahydrogestrinone, also known as "The Clear." Jones claimed she believed she took a flaxseed oil supplement, but her admission in 2007 proved she lied to investigators and had to face the consequences.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

She spent some time behind bars

Marion Jones' press conference came after she pleaded guilty to two counts of making false statements to federal agents, so she didn't come clean without cause. Had she gone to trial, Jones faced a significant prison sentence, but her plea deal reduced her time behind bars. Jones earned herself a six-month prison sentence, two years of supervised release, and 800 hours of community service. In her admission of guilt to the court, Jones said, "I absolutely realize the gravity of the offenses I've committed" (via ABC News).

Jones begged the judge to limit her time behind bars, hoping not to be separated from her children. Prosecutors recommended zero to six months of confinement, so the judge handed down the maximum-requested sentence "because of the need for general deterrence and the need to promote respect for the law" (via BBC News). Jones reported to jail on March 11, 2008, and was released on September 5, completing 178 days of her 180-day sentence.

Jones' crimes weren't limited to lying to federal investigators about her steroid use. She also pled guilty to lying to investigators related to a check-counterfeiting scheme. Records showed that Jones deposited $25,000 from her ex-boyfriend, Tim Montgomery. Her false statements during the investigation revolved around her stated ignorance regarding the scheme, but financial documents proved otherwise, so she admitted to lying in that investigation as part of her plea deal in 2007.

Her previous victories were revoked

After publicly admitting to lying for years about her steroid use, Marion Jones found her career at an end. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency handed down a two-year suspension from track and field competition, but Jones took it a step further and officially retired from the sport. That was only the beginning because the USADA also sanctioned Jones by disqualifying every one of her achievements, beginning on September 1, 2000, requiring the forfeiture of everything she earned, including points, prize money, and medals.

Soon after, the International Olympic Committee stripped Jones of her medals and removed her stats from Olympic records. Peter Ueberroth, chairman of the U.S. Olympic Committee, issued a statement demanding Jones return her medals. "As further recognition of her complicity in this matter, Ms. Jones should immediately step forward and return the Olympic medals she won while competing in violation of the rules" (via Reuters).

Jones returned her Olympic medals in October 2007, though it's unclear how the handoff went down. The IOC's decision came a month after the International Association of Athletics Federations erased Jones' stats going back to September 2000. Essentially, every achievement Jones made after the date of her admitted steroid use became suspect and was voided entirely from the records. Her stats before September 2000 remain intact.

She lost a lot of money

Marion Jones' admission of guilt in the BALCO investigation and counterfeit-check scheme brought significant financial costs. Not only did Jones have to defend herself through expensive attorneys, but she also lost out on various revenue streams. By June 2007, the Los Angeles Times reported Jones had around $2,000 in her bank account. On top of having little liquid assets, Jones lost her $2.5 million mansion in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, due to a bank foreclosure. Additionally, she sold two properties to raise money.

Jones lost a countersuit brought by track coach Dan Pfaff, resulting in a $240,000 judgment for unpaid fees and expenses. While defending herself before her admission of guilt, Jones missed out on five international competitions, losing around $300,000 in appearance fees. The loss of income only made Jones' financial difficulties harder to overcome. At her height, Jones earned as much as $80,000 per race and as much as $1 million in endorsement deals.

As a top-tier athlete in track and field, Jones had several high-profile endorsements early in her professional career. All her endorsement contracts, including one from Nike, dropped Jones in 2007. The company declined to recover the money it paid Jones, but losing the contract hurt her bottom line. In addition to returning her medals, Jones was ordered to repay $700,000 in prize money.

She joined the WNBA

Before focusing her professional career on track and field, Marion Jones was an NCAA basketball champion. Jones played three seasons with the North Carolina Tar Heels, which won the NCAA Division I women's basketball championship in her freshman year. With her career in track and field over, Jones returned to her roots and trained with the San Antonio Silver Stars in October 2009, hoping to find her way into the WNBA.

The New York Times broke the news of Jones' interest in returning to basketball, and Jones explained someone called her asking if she'd be interested in playing in the WNBA. "I thought it would be an interesting journey if I decided to do this, Jones said. It would give me an opportunity to share my message to young people on a bigger platform; it would give me an opportunity to get a second chance." Jones eventually got that chance when the Tulsa Shock signed her in 2010.

Jones played point guard for the Tar Heels and played guard for the Shock. She played 47 games, but the Shock cut her before her third season. Jones' stats didn't measure up, having averaged less than one point per game in the 14 appearances of her second season with the team. Incidentally, the Tulsa Shock wasn't the first WNBA team interested in Jones. The Phoenix Mercury selected her in the 2003 WNBA draft, but she wasn't signed and never played any games with the team.

She published her memoir in 2010

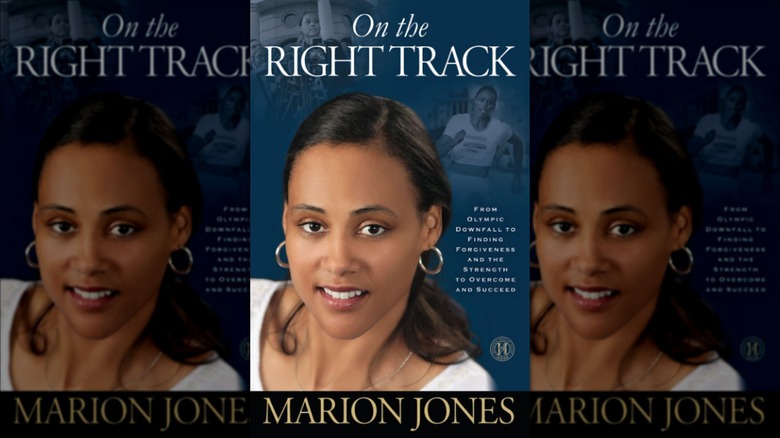

Marion Jones published her first book, "Marion Jones: Life in the Fast Lane — An Illustrated Autobiography," in 2004. The book includes passages related to her then-purported drug use, though this may be the one line that truly didn't age well: "I am against performance-enhancing drugs. I have never taken them, and I never will take them." Of course, the story eventually changed, and Jones' drug use found confirmation via the BALCO investigation and its aftermath.

Jones wrote while in prison, mainly penning letters to her husband and children. When she got out, she continued writing and developing her memoir, published in 2010, "On the Right Track: From Olympic Downfall to Finding Forgiveness and the Strength to Overcome and Succeed." The most significant difference between the two books is Jones' honesty about her past. In it, she addresses the many lies she told over the years, how she fell into a pattern of dishonesty, and how it impacted her life.

Her memoir also details her experiences in prison, writing about being attacked shortly after arriving: "I felt like my life was in danger. And I just lost it. I hit her [another inmate] in the face with my cooler and kicked her in the ribs." She got over a month in solitary confinement, otherwise known as the "hole," following the fight, which she described as "the next stop to hell," according to The Sydney Morning Herald.

She became a personal trainer

Marion Jones' life saw many highs and lows, beginning in college as an NCAA champion. She became "the fastest woman in the world" after winning five medals at the 2000 Olympics, so if she had a true career height — that was it. Still, she continued competing and participated in the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Greece, but didn't place in the top three. Regardless, her career continued right up to the point it all came crashing down, and a brief stint in the WNBA didn't turn it all around.

Jones and her family settled in Pflugerville, just outside of Austin, Texas, and she took a job with Camp Gladiator. Camp Gladiator is an outdoor fitness training program designed for adults of any fitness level. Jones' Camp Gladiator page lists her fitness background as a "Former Olympian and Collegiate National Champion," and she calls herself a "COACH" and not just a personal trainer.

In addition to working as a personal fitness trainer, Jones takes any opportunity she can to connect with the youth of her community. In February 2020, Jones accepted an invitation to be the main speaker at the Delco Elementary School in northeast Austin. She spoke during the school's Black History Month program, telling the children the importance of taking a break and thinking before making a pivotal decision, which has been her central message since coming clean about her drug use.