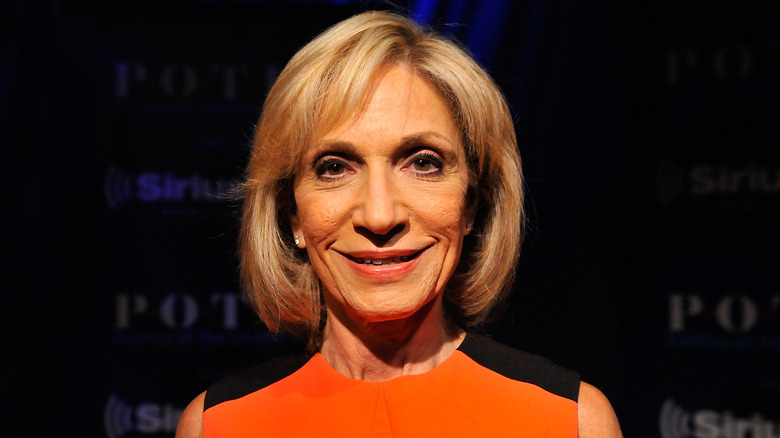

What Andrea Mitchell's Husband Alan Greenspan Really Does For A Living

Andrea Mitchell has a monogamous relationship with NBC, the network she has been with since 1978. She's no different in her personal life. Mitchell has been with Alan Greenspan for nearly four decades, having met in 1983 when she interviewed him. They started dating in 1984, maintaining a long-distance relationship until 1987, when Greenspan moved to Washington, D.C., where Mitchell covered the Ronald Reagan administration. In April 1997, Mitchell married Greenspan in a ceremony officiated by none other than the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The wedding marked the second marriage for both of them. Mitchell had been married to Gil Jackson, acting as the stepmother to his two sons until they divorced in the mid-1970s when she left Philadelphia for D.C., according to Broad Street Review. But Mitchell doesn't publicly acknowledge her first husband, who has since died. Before marrying the veteran journalist, Greenspan was briefly married to another Mitchell — the Canadian painter Joan Mitchell. The pair tied the knot in 1952, though the marriage lasted only 10 months.

Greenspan went on to date another famous journalist: the late Barbara Walters. The relationship ended a few years before he found his long-term partner and future wife. It's no coincidence that Greenspan's been associated with so many high-profile figures. While not everyone might know his name today, Greenspan's illustrious career has earned him quite a reputation. He has even been described as a "rock star," not exactly a common adjective for someone with a such a serious job.

Alan Greenspan chaired the Federal Reserve for almost two decades

From 1987 to 2006, Alan Greenspan served five terms as chairman of the Federal Reserve. That means that four different presidents — Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush — considered him fit to dictate the monetary policy of the world's biggest economy. As such, Greenspan acted as one of the most influential civil servants worldwide for 18 years. During those years, Americans could count on Greenspan — a Republican — to have an opinion.

His passionate defense of the privatization of Social Security and tax cuts earned him criticism for politicizing the office. But his productive tenure remained untarnished through the end. While he retired in January 2006, Greenspan continued to work in the field as a consultant through his firm Greenspan Associates, LLC, in Washington, D.C. In May 2007, Pacific Investment Management Co. brought on Greenspan as a special consultant. Three months later, he became a senior advisor for Deutsche Bank.

The following year, Greenspan also joined the hedge-fund firm Paulson & Co. as an advisor. No one was surprised he was still sought-after following his retirement. "He is a very great source of everything economic," Richard Yamarone, an economist at Argus Research Corp, told the Associated Press in 2005. "It would be imprudent not to tap that resource." For close to two decades, Greenspan maintained his status as "Maestro" of the U.S. economy, as Bob Woodward titled his book about him. But that changed shortly after his retirement.

The threat to Alan Greenspan's rock star status

Alan Greenspan kept the U.S. economy afloat through some turbulent waters. For his ability to keep the country stable while the world tumbled, Greenspan earned massive respect across party lines. "He almost has rock star status," Mark Zandi, chief economist at Economy.com, told the AP. "He has everything but the groupies." That is, until the economy crashed amid the 2008-09 recession, just two years after the end of his tenure as Fed chair.

Greenspan was criticized for his role in encouraging Americans to take out variable-rate home loans in 2004, which many argue contributed to the housing bubble that led to the crash, Rolling Stone noted. Pretty much overnight, Greenspan went from hero to villain. Barbara Walters, his old girlfriend, said she was anything but surprised. In 2007, she joked on "The View" that he'd always been bad a giving real estate advice.

In 1977, Greenspan advised Walters not to spend $250,000 on an apartment on Fifth Avenue. "'Don't buy it,' he said. 'The way New York City is going, it's not a good investment," Walters wrote in "Audition," her 2008 memoir. "So I didn't buy it. Today that apartment is worth at least $30 million." Unlike Walters, Andrea Mitchell has kept her opinions to herself. She had to, as many questioned whether she could continue to do her job fairly. "She knows where to draw the line," Steve Capus, the then-president of the division, told The New York Times.