Whatever Happened To Crazy Eddie?

This feature references alcohol misuse.

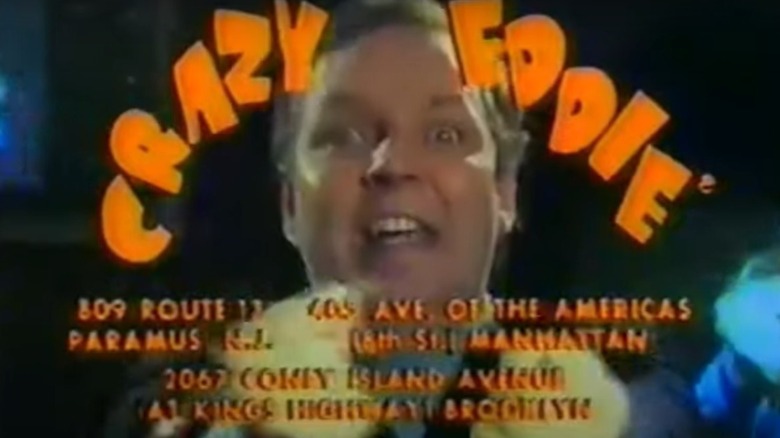

"Crazy Eddie, his prices are in-s-a-a-a-ne!" Anyone who listened to Tri-State area radio during the 1970s and 1980s will no doubt remember the zany commercials for the chain of bargain electronics outlets named after its co-founder Eddie Antar.

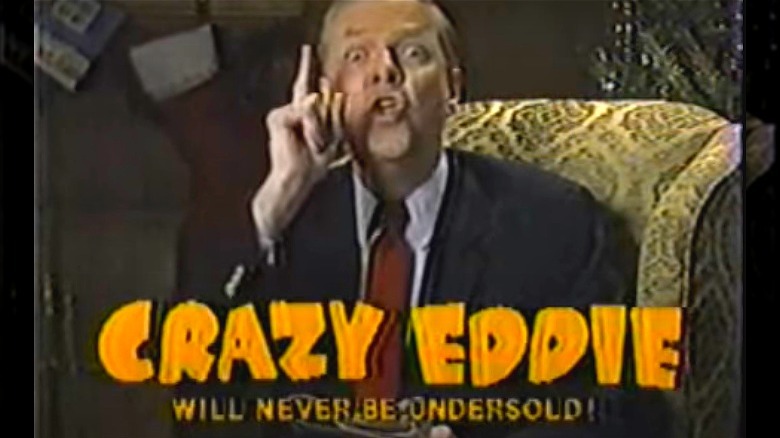

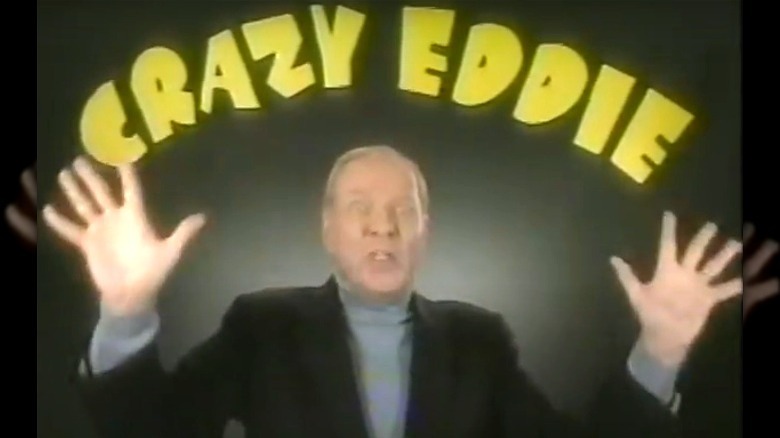

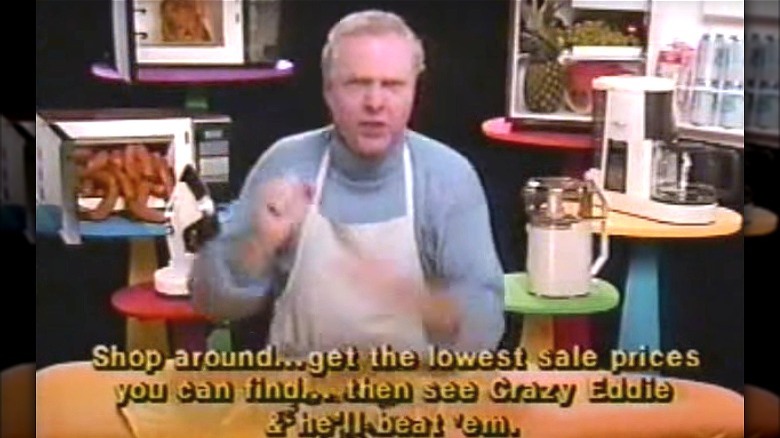

The ads, which saw New York DJ Jerry Carroll portray the entrepreneur in a manner that is best described as maniacal, were never off the airwaves at the time. And as highly irritating as they could be, they did a great job in promoting the brand: Crazy Eddie reported sales of over $300 million during its heyday and was able to open up a total of 43 shops across four states. They were even parodied on "Saturday Night Live!"

However, Antar's rags-to-riches story eventually went sour. From prison sentences and international escapes to extra-marital affairs and multiple comebacks, here's a look at how he and his eponymous company truly lived up to his crazy nickname.

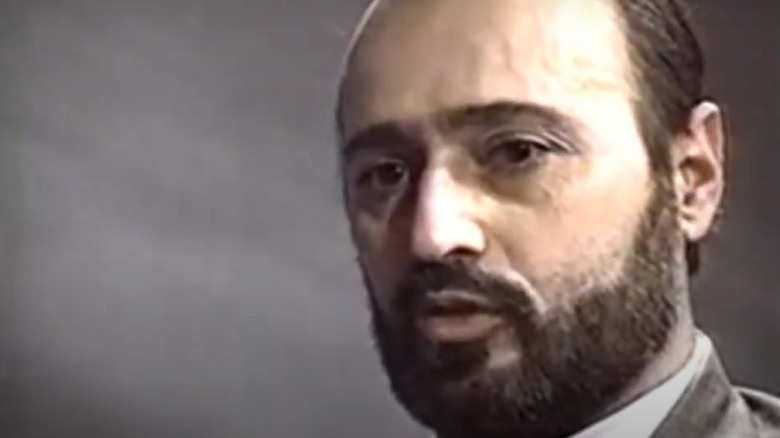

Who was Eddie Antar?

Founded by father and son team Sam M. Antar and Eddie Antar, Crazy Eddie was a Brooklyn electronics discount store first known as Sights and Sounds when it opened in 1969. It adopted its more familiar moniker two years later and due to the success of its radio and small-screen ads — in which Jerry Carroll took on the role of the overly-enthusiastic salesman named Crazy Eddie — it eventually expanded across northeastern America.

Each new store opening was greeted like a monumental pop culture event. Harry Spero, who worked for the company's advertising department, told author Gary Weiss for the biography "Retail Gangster," "We would promote the hell out of them, and there would be lines 'round the block for people to get a free T-shirt." During one opening in East Brunswick, approximately 20,000 locals turned up!

Crazy Eddie was able to offer such insane prices due to Eddie's unscrupulous business tactics. Rather than buy his products from reputable dealers, he would acquire them from similarly underhanded organizations such as the North Bronx's Corner Distributors, as well as international vendors. Because Eddie's overheads were much smaller than his rivals, he was able to offer consumers prices just above their wholesale value.

Was Eddie Antar really crazy?

Eddie Antar apparently objected to being called crazy. Yet there are several examples of this tag being justified. While some were relatively innocuous, like the good luck charm ripped sweater that he sported pretty much every day for two years in a row, he was also something of a persistent salesman. "I wouldn't let a person walk out the door without selling," he once admitted, per "Retail Gangster."

But most of his practices were questionable at best, and downright illegal at worst. For example, Eddie stole the Crazy Eddie logo from revered cartoonist R. Crumb without ever offering any compensation (according to "Retail Gangster," years later, Crumb would admit about the logo, "I was sort of flattered by such borrowing of my cartoon images back then"). Eddie also once bought a medical school in the Caribbean that was not only in a significant amount of debt but was additionally the subject of a federal lawsuit. And his personal life was just as messy, too.

In 1977, an inebriated Eddie, who had a long-standing problem with alcohol misuse, received a stab wound to the abdomen after getting into an altercation outside a club. And then there was the fact he had a wife and a mistress, both of whom were named Debbie, a state of affairs that came to a head during a major family fight dubbed the "New Year's Eve Massacre."

The New Year's Eve Massacre

The New Year's Eve Massacre of 1984 was essentially instigated by family patriarch Sam Antar who, after learning that his son was having an affair, ruthlessly engineered a confrontation between Eddie and the two women in his life — his wife, Debbie I, and his mistress, Debbie II. In the event of a divorce, Sam's one-third stake in the company had the potential to fall to Debbie I, giving Sam a reason to fire him before that could happen, thus securing his stake in the company.

His dastardly scheming appeared to work when Debbie I and Eddie's sister discovered the entrepreneur waiting in a limo for Debbie II on Manhattan's East 80th Street. The subsequent slanging match resulted in Eddie giving his sibling a slap across the face, and fleeing just before the cops arrived on the scene.

In a tactic he'd apparently used countless times in his business endeavors, it was discovered that Sam had tricked Debbie I into putting her name on divorce papers that left her short on cash despite previously being promised a 50% split. In 1987, Debbie I would be one of the first to accuse Eddie of fraud for his financial trickery with The New York Times reporting that she was reopening their divorce settlement. She claimed that her husband had hidden his apparent $10 million annual income from her when she agreed to an alimony amount and child support for their five daughters. But this was only the beginning.

The fraud begins

While Crazy Eddie presented itself as a family-friendly store, behind the scenes it was a den of inequity. And from essentially the moment that its first shop opened its doors, the company started engaging in fraudulent activity. Per the Financial Post, co-founder Eddie Antar and his involved family members would purposely falsify their accounts to save on their income taxes. They'd pay their workers off the books, and take one dollar from every five reported as income. They also deposited much of their ill-gotten gains in offshore bank accounts, stashing away $6 million between 1980 and 1983.

The company went public in 1983 in a bid to cover up its illicit activities, a tactic that initially appeared to work. Within three years, the shares that had initially been sold for $8 had grown in worth to $75. Then there was the infamous tactic known as the Panama Pump which involved Eddie flying to Israel with wads of money strapped to his body which he then deposited in a bank. Per The New York Times, this cash was then sent back to Crazy Eddie via Panama, subsequently fooling analysts into believing the firm was simply doing exceptionally well.

But the Antars' greed eventually got the better of them and their extraordinary falsified figures began to attract suspicion. Later that same year, Eddie announced he was stepping down as CEO and president of Crazzy Eddie while staying on as chairman.

The hostile takeover

In 1987, Elias Zinn, the owner of a Texas-based discount electronics chain, and Victor Palmieri, a management consultant, purchased 7.5% of outstanding Crazy Eddie shares. This allowed the pair to stage a hostile takeover, something which Eddie Antar and his cousin Sam Antar decided to fight against. The two were understandably worried that having an outside party muscle in on their business could uncover the family's various frauds.

Writing on his website White Collar Fraud, Sam explained, "We needed a friendly party to help us keep control of the company. Our plan was to raise outside money and take the company private with an unsuspecting third party in an effort to cover up our frauds. We would not have to invest a dime of our own money to take over the company, since the new investors and Wall Street investment banks could potentially bankroll a management-led takeover of Crazy Eddie."

But their efforts proved to be futile and in November later that year, Zinn was announced as Crazy Eddie's new owner. If that wasn't bad enough, the Antar family was also hit with multiple stockholder lawsuits after financial analysts began to dig deep into the company's books. While those filing such suits had lost a significant amount of money in the past three years, Eddie had sold enough shares to make himself $74 million richer, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Crazy Eddie goes into liquidation

You likely won't be surprised to learn that once Elias Zinn took over Crazy Eddie at the end of 1987, he also removed any of the remaining Antar family members. But he was no doubt soon left wishing that he'd left the company well alone.

In March 1989, Crazy Eddie was forced to shut 17 of its stores as its financial problems continued to grow. Per the Los Angeles Times, three months later, several creditors — owed a combined total of $860,000 — filed a petition to send the firm into bankruptcy. Within a fortnight, Zinn and Co. decided to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection voluntarily. Peter Martosella, the new CEO, vowed to keep the company going. But as their number of stores dwindled, and with suppliers unwilling to do business, Crazy Eddie became a lost cause.

In October of that same year, the firm went into Chapter 7 bankruptcy followed by the liquidation process, and a once-inescapable part of the Tri-State area's retail industry was officially no more. A spokesperson told The New York Times that the company's fate was essentially determined by increased pressure from financial entities, explaining, "It was the consensus of the creditors that given the softness of the market, that they couldn't extend further credit."

The real start of Eddie's legal problems

While this was the end of the Crazy Eddie story (for now, anyway), it certainly wasn't the end of the Eddie Antar story. Tipped off by Arnie Spindler, a disgruntled former associate, the Securities and Exchange Commission looked further into the firm's illegal activities and subsequently charged its former owner with insider trading and security fraud, per Crain's New York Business.

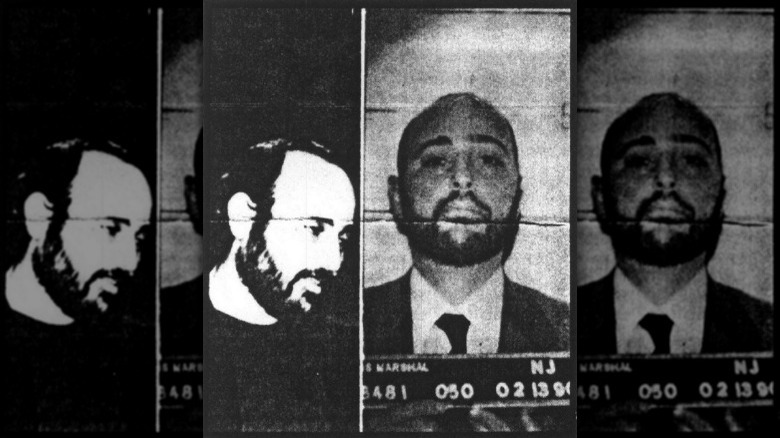

At the start of 1990, a Federal district judge ordered Eddie to recover the $52 million sum that was believed to have been transferred to Israel. He was also ordered to appear in court to explain himself. However, the entrepreneur still refused to play by the rules, and after failing to show up on the scheduled date he was hit with an arrest warrant, as reported by The New York Times.

Eddie did hand himself in within a week to the U.S. Marshals. But once again, he couldn't resist trying to dodge justice. When the businessman became a no-show at a follow-up hearing, he was hit with another arrest warrant and the freezing of his entire assets.

Catch me if you can

Remarkably, Eddie Antar continued to give officials the runaround for the next three years. He fled to Israel, the country where he'd deposited most of his Crazy Eddie stocks money, with a false passport under the name of David Jacob Levi Cohen. He was even said to be living in a luxurious townhouse there. Eddie's cousin, on the other hand, decided to come clean with authorities, albeit for an immunity deal.

Indeed, after agreeing to testify against his own sibling for the Federal prosecution and pleading guilty to several felonies, Sam Antar was sentenced to a 1200-hour community service program, a three-year probation period, and house arrest for six months. In a piece on his White Collar Fraud website, the defendant claimed that he was put in the firing line by his relatives. "Eddie, Mitchell, and Allen tried to lay the entire blame for the Crazy Eddie fraud on me, despite them and other immediate family members pocketing over $90 million of ill-gotten proceeds from selling Crazy Eddie stock at inflated values to defrauded investors and millions of dollars uncovered in secret foreign bank accounts."

Incredibly, in a move that echoed the subject of Leonardo DiCaprio's "Catch Me If You Can" protagonist Frank Abagnale Jr., Sam went on to work as a government advisor on the issue of fraud investigation. The path that Eddie took, however, meant that he was never going to be offered such a position.

Eddie faces justice

In 1992, Eddie Antar was finally brought to justice when he was arrested and extradited from Israel back to the U.S. on federal racketeering charges, per UPI. Unlike his cousin, the Crazy Eddie owner decided against pleading guilty, and a year later his case went to trial.

While Sam managed to evade any time behind bars, Eddie was given a prison sentence of 12 and a half years after being found guilty of no fewer than 17 different counts of fraud, per The Washington Post. But things are never straightforward with the Antars and after lawyers contested the verdict, a retrial was set. As The New York Times reported, the federal appeals panel concurred that the original trial judge had displayed prejudice in their ruling against the entrepreneur. The second time around, Eddie decided to plead guilty, and at the start of 1997, he was given a lesser eight-year prison sentence. The businessman still had to pay litigation recoveries of more than $150 million, though. According to White Collar Fraud, the various civil suits against the family exceeded $1 billion.

In 2007, a CNBC "Business Nation" special somehow managed to bring Eddie and Sam together for a heated televised reunion. When asked whether he could forgive his cousin for testifying against him, the former said, "I forgave him a long time ago. ... When people live in the past, you know what it does to you, it sucks you into a black hole. It destroys you and crushes you." Sam, on the other hand, said he couldn't return the favor as he hadn't forgiven himself.

Eddie Antar still protested his innocence

Although Eddie Antar pleaded guilty to racketeering in court, he still claimed to be innocent of fraud to the press. Shortly after being sentenced for the second time, the businessman told the New York Post that he had no involvement in any fraudulent activities. He also claimed that Crazy Eddie had gone into bankruptcy because of its new owners and that he'd actually left it as a "healthy company, a cash machine."

The fact that Eddie had spoken to the media at all was something of a surprise. Unlike Jerry Carroll, the man hired to sell Crazy Eddie on radio and television in the loudest manner possible, the man dubbed the "Darth Vader of Retail" by the prosecutor of his federal case was someone who preferred to keep away from the spotlight.

Indeed, as revealed in a 1985 The New York Times piece, Eddie didn't even have his photo taken for the annual Crazy Eddie shareholder meeting. Analyst Edward Weller told the newspaper why he believed the entrepreneur was so reluctant to be publicized, saying, "He is very smart, very aggressive, but self-conscious. He has a strong sense of just having gotten lucky, and he is not sure it's all exactly for real."

Crazy Eddie returns

You'd expect that the Crazy Eddie name would be too tarnished for any comeback to ever be launched. But there have actually been several attempts to bring back the electronics discount store since it went into liquidation in the late 1980s.

It was two of Eddie's nephews, Sam A. Antar and Adam Kuszer, who got the closest to restoring the company's former glories. In 1998, the cousins opened up a Crazy Eddie outlet in the New Jersey township of Wayne as well as an online store, with the former telling The New York Times, "I worked in the stores as a kid, and ever since then I've loved electronics. Now it's our turn to come back into the business.” They even managed to bring Jerry Carrol back, the man who'd voiced all those "prices are insane" ads, to help promote the venture.

However, some experts such as Goldman Sachs retail analyst David Bolotsky remained skeptical about the relatives' chances. "There is still a tremendous amount of awareness surrounding that name," they told the publication. "Who knows? There could be a little nostalgia for the go-go '80s.” Sadly, those fears were founded as within a year, the new Crazy Eddie had gone the way of the previous 43 shops.

Crazy Eddie returns... again

In 2001, two years after being released from jail, Eddie Antar returned to the scene of his crimes by working on the online and telephone order sides of Crazy Eddie, which unlike his nephews' bricks-and-mortar outlet had survived beyond a year.

According to "Retail Gangster" (via the New York Post), Eddie believed that the web version of the electronics discounter would prosper once more and again sought the help of Jerry Carroll to tap into any remaining nostalgia for the tarnished Crazy Eddie brand. But unsurprisingly, investment was hard to come by and in 2004, crazyeddie.com was defunct. As you can probably guess, this wasn't the end of the protracted saga.

In 2006, Trident Growth Fund attempted to auction the brand for $800,000 when it bought Crazy Eddie's IP but failed to convince anyone to take it on — the highest bid was just $30,100. Jack Gemal, a Brooklyn entrepreneur, did take things further when he acquired the Crazy Eddie name three years later and launched the pricesareinsane.com website. But his plans to open 50 accompanying physical stores never got off the ground and his online venture also collapsed. As of 2023, this is the last Crazy Eddie-affiliated business.

Eddie Antar dies

The Crazy Eddie saga appeared to end in 2016 when its founder Eddie Antar died at 68. But even in death, the entrepreneur was still causing chaos and confusion. Indeed, depending on which family member you ask, Eddie died of either liver cancer or cirrhosis of the liver, potentially caused by his drinking habits. Despite the fraudulent activities that led to jail time, the eulogies for Eddie in the press were unexpectedly a little adulatory. The New Yorker's Michael Schulman wrote, "I'm wistful for Crazy Eddie ... Back then, at least, chain stores were weird." Meanwhile, CNBC's Herb Greenberg tweeted that Eddie's death marked "The end of an era ... Love him [or] hate him, he was an original."

In his 2022 book, "Retail Gangster," Gary Weiss summarized why the troubled entrepreneur still had such a hold on certain members of the public. "Eddie's brainchild was a screaming ghost of the past, emblematic of a vanished working-class New York ... a lethal, exciting city that was deeply, exuberantly crooked." As the biographer put it, while Crazy Eddie and the man behind it were undoubtedly shady, the story's bizarre legal and personal intricacies held an unyielding fascination that couldn't be denied. Weiss wrote, "Eddie Antar was the fever dream you try to remember even though it was grand and scary and made no sense."

Could Eddie Antar have got away with the scam today?

You might think that Eddie Antar couldn't have gotten away with all his unscrupulous activities in an age when computing has progressed beyond the capabilities of the '70s and '80s. But Gary Weiss, who wrote the book "Retail Gangster" about the Crazy Eddie saga, believes that isn't the case.

Speaking to The Times of Israel, the writer claimed, "I don't think there would have been any difference. I don't think analysts are any more skeptical than they were 30 years ago. I don't think the public is any more skeptical. I don't think regulators are any better, I don't think the accounting firms are any better." The author went on to claim that the same commercial and regulatory bodies that Antar was able to hoodwink are still attractive to scam artists existing today.

As an example, Weiss pointed to a more recent, and arguably much bigger, crook as an example, adding, "The proof of that, I guess, would be [Bernie] Madoff... [who] was able to keep the scam going until the first decade of the 21st century." Per The Guardian, Bernie Madoff is renowned for running one of the largest Ponzi schemes in history. In 2009, he was sentenced to 150 years in prison after pleading guilty to fraud a year earlier. He was accused of having scammed an estimated $17.5 billion from investors — many of whom had trusted their life savings to him as part of the scheme.

Is the Crazy Eddie story heading for Hollywood?

We've had the book, now get ready for the film. Well, maybe. In 2019, Entertainment One announced that it was greenlighting "Insane" a dramatization of the Crazy Eddie story which would be helmed by "The Meg" director Jon Turteltaub and scripted by "21" writer Peter Steinfeld. The film was said not to be told from the perspective of jailed founder Eddie Antar but from that of his crook-turned-forensic accountant cousin Sam Antar, who was also serving as the film's executive producer. As of this writing, the project appears to be stuck in development hell, and there's been no further word about its casting or production.

This wouldn't be the first time that a Crazy Eddie movie has failed to get off the ground, though. In 2009, none other than Danny DeVito revealed he was hoping to take the crazy story to the screen with the help of the then-still-living Eddie himself. However, amidst fears that real-life investors in the defunct electronics discount store would seek legal action, the idea was nipped in the bud a year later.